The Unified Theory of Humor

For many people, humor is difficult. It is often mysterious. Most are content to allow it to remain a mystery, but NOT ME! As with most things, I am compelled to analyze it to death. In doing so, I have reached a theory:

Humor is the creation of a certain range of cognitive dissonance ("CD"). Too little CD, and it doesn't have much of an effect. Too much CD, and we feel uncomfortable or confused. But almost everyone has a sweet spot where just the right amount of CD can inspire laughter.

“I know why we laugh. We laugh because it hurts, and it's the only thing to make it stop hurting.” -- Robert Heinlein

What is Cognitive Dissonance?

According to Wikipedia, "cognitive dissonance is the excessive mental stress and discomfort experienced by an individual who holds two or more contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values at the same time." Cognitive dissonance is a concept that is familiar to many atheists, as it is often starkly encountered among the religious. For instance, many religious people believe that God is all-knowing, all-just, and all-powerful, yet they also believe that evil exists in the world or that their actions have meaning. Attempts to engage in conversation on this topic with religious people are often met with evasions, anger, and/or changing the subject, as it causes people stress to dwell on contradictory ideas.

The magnitude of cognitive dissonance produced depends on two factors: Factor 1: the personal value that a person puts on each belief; and Factor 2: the proportion of dissonant to consonant elements in the two beliefs. To produce maximum CD, the two conflicting beliefs should both be monumentally important but completely opposite (e.g. you will be rewarded in the afterlife/there is no afterlife). Small amounts of CD can be produced by beliefs which are frivolous and only slightly incompatible (e.g. green & blue don't look well together/a person on the street looks good in green & blue).

Humor tends to work best with moderate levels of dissonance from each factor, though certain types of humor can get by reliance only on a single factor (predominantly Factor 2).

Examples of Cognitive Dissonance in Humor

In humor, cognitive dissonance is most often inspired by subverting our expectations (playing off of Factor 2). Many classic forms of humor rely on the idea that something unexpected happens. Monty Python has basically made a career out of absurdity. South Park successfully lampooned the show Family Guy by pointing out that all of their humor was basically a confluence of four or five different random words, which were only funny because people didn't know what to expect, which created a good amount of dissonance from Factor 2.

Parody (where a work intentionally mimics another) works as humor, but only where one is familiar with the work being parodied. The original work lets us know what to expect, and then the parody deviates in ways that are (hopefully) unexpected, resulting in humor! Puns work the same way. We know what to expect, but then we get something different. Funny!* With all of these, comedians and writers tend to use various subject matter with varying levels of success, as different subject matter will inspire different levels of dissonance from Factor 1.

Double entendre is funny because it involves something that means two things at the same time, creating dissonance. However, double entendre is only slightly dissonant regarding Factor 2. After all, lots of words have multiple meanings, so it's not that out of the ordinary. Because of that, the second meaning has to be a wildly inappropriate thing to say in the given context (usually something sexual), so it creates CD from Factor 1 also, bolstering the joke. In a society that was more comfortable with sex, sexual double entendre wouldn't be funny.

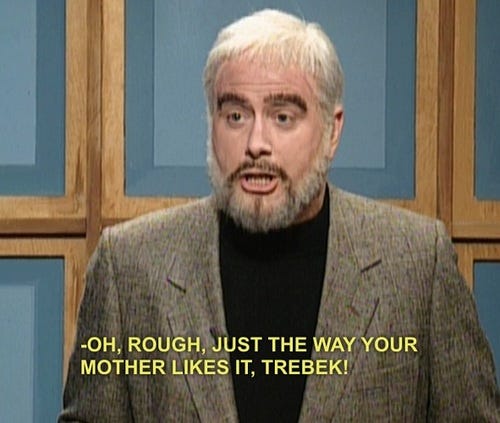

Satire works like parody, but it increases the value of the conflicting beliefs (Factor 1) and decreases their incompatibility (Factor 2). This is why when you see Sean Connery on SNL's Celebrity Jeopardy, he has to be wildly over the top with his racism, stupidity, and aggression (parody), while Senator Bulworth can be much less of an extreme character (satire) because the subject matter he's making fun of (politics) is so much more important than the antics of celebrities on gameshows.

Slapstick humor tries to walk the line right between funny and tragic. It works best when the pain is unexpected, which causes dissonance from Factor 2. Then to succeed, it has to cause enough pain to inspire some dissonance from the Factor 1, but no so much pain that it causes too much dissonance. So, guy getting hit in the nuts, but no permanent damage? Funny. Guy getting head blown off? Not funny. BUT, you'll notice, that people who are especially empathic or who have more personal experience with physical pain tend to find slapstick humor less funny. This is also the reason why pain caused to cartoon characters can be much worse than live-action characters and still be funny. We know there will be no permanent damage, so we never really get to uncomfortable levels from Factor 1.

The Unified Theory Explains Humor Fails

[CN: this section discusses rape jokes]

Because everyone's starting place is different, different people are going to experience varying levels of CD at the same joke. Mainstream tv jokes try to go for the largest appeal possible, so they tend to focus on areas that (in the writers' estimation) are near-universal in the target demographic (which is why so many jokes are about heteronormative relationships). However, I've seen it often where a sizable minority won't find something funny, either because (a) they find it more or less dissonant than the minority (Factor 2), or (b) they find the dissonant ideas more or less important than the majority (Factor 1).

This explains why gay jokes (specifically, jokes about how a masculine male character was gay) were all the rage in the early 90's, but have since fallen off. In the early 90's, in the eyes of the majority, gay people were a strange, alien "other," so the suggestion that a "normal" man was gay would be very dissonant. The effect was magnified by the fact that being gay was seen, for men, as the worst possible thing to be, so the value difference between the two dissonant ideas ("he's gay" vs. "he's not gay") was huge for the majority of Americans. However, as dominant cultural attitudes have shifted, such jokes have lost their potency. Currently, we're in a situation where part of the population is still in early-90's mode, but a large part of the population understands that being gay is not particularly absurd or problematic, so we don't see the "joke" as funny. Further, people intuitively understand some of what it would take for the joke to be funny, so we get offended at the suggestion that being gay is something to laugh at.

The same thing happens with rape jokes. To decent, well-informed people, rape is horrifically tragic and widespread. However, certain segments of the society see rape as (a) something that doesn't happen to nice girls who take care of themselves, and (b) no big deal. So when Daniel Tosh says "Wouldn’t it be funny if that girl got raped by like, 5 guys right now?" it fails on two levels for decent people: (a) a woman getting raped isn't out of the ordinary, so it doesn't subvert our expectations and creates very little dissonance from Factor 2, and (b) the value difference between the two conflicting ideas (girl gets raped vs. girl doesn't get raped) is ASTRONOMICAL, so it sends the dissonance level from Factor 1 into the stratosphere. However, for dudebros like Daniel Tosh, the idea that she would actually get raped is absurd AND he doesn't really care all that much if she gets raped, so it seems funny to him.

One of my favorite types of humor (and one of the easiest to screw up) is countersignaling. As Scott Alexander explains in the linked post, "countersignaling is doing something that is the opposite of a certain status to show that you are so clearly that status that you don’t even need to signal it." Alexander's post discusses how people who are good friends will often say mean, cruel things to one another as a way to show what good friends they are. For me, that sort of thing hits my sweet spot of CD like nothing else. I get a good amount from Factor 2 because a good friend is behaving like they hate me, and I also get a good amount from Factor 1 because it's important to me that my good friends like me. However, it doesn't go to uncomfortable levels because I know it's a joke, so I don't REALLY start questioning my belief that this person is my good friend.

However, countersignaling goes horribly wrong when you haven't built up that kind of credibility with your audience. Often, attempted countersignaling will be seen as sincere, which ratchets up the CD from Factor 2 to seriously uncomfortable levels. I can't tell you how many people I've offended by attempting countersignaling humor too early in our relationship, before I've made it clear that I would never say those things in earnest. Seriously. It's a problem.

Conclusion

There is no formula for humor. Humor is tough, and extremely audience-dependent. However, my hope is to understand it a little more, and I think this lense allows me to do that. What do you think?

____________________

*anyone who wants to argue that puns aren't funny can GTFO right now. Puns are the best.