Book Review: Bad Therapy

Bad Therapy: Why the Kids Aren’t Growing Up is Abigail Shrier’s latest entry in the culture war. Her previous entry was Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters, which I did not read and have no plan to, but the title seems to pretty clearly communicate where it’s coming from. Bad Therapy is a similarly critical take on one of the Left’s favorite things.

As the title suggests, the book is critical of the mental health industry. But that’s really only half of it. The other half is an indictment of “gentle parenting.” Her thesis seems to be that therapists have convinced all the parents that doing any real parenting is Bad and Wrong, where “real parenting” is, like, yelling? And ignoring your kids. Also spanking. She has a real thing about spanking. She never actually comes out in favor of spanking, but keeps bringing it up as something parents used to do in the good old days and how really, it isn’t so bad.

The book is interesting because it contains numerous valid criticisms of the way our children are overdiagnosed, medicalized, and medicated mixed with a bunch of nonsense about how The Kids Today just need discipline or whatever.

Shrier comes out swinging in the introduction, with passages like

We rushed our kids back to the mental health professionals who had guided our parenting, this time for testing, diagnosis, counseling, and medication. We needed our kids and everyone around them to know: our kids weren’t shy, they had “social anxiety disorder” or “social phobia.” They weren’t poorly behaved, they had “oppositional defiant disorder.” They weren’t disruptive students, they had “ADHD.” It wasn’t our fault, and it wasn’t theirs. We would attack and finally eliminate the stigma surrounding these diagnoses. Rates at which our children received them soared.

You can tell right away that this is a work of persuasion, not an evenhanded look at the evidence. When you read a Scott Alexander deep dive, there are detailed looks into scientific studies, examinations of the quality of the evidence, and a constant acknowledgement of what remains unknown. This book is not like that. Its bread and butter are interviews with supposed experts, often weirdly including details about what they were wearing or how attractive they are, and illustrative anecdotes. This is, unfortunately in my experience, just how these books are written. Books about the social sciences written for a mass audience seem to require a lot of fluff and irrelevant details, and this one is no exception.

The closing of the introduction sets the tone for the rest of the book:

With the charisma of cult leaders, therapeutic experts convinced millions of parents to see their children as challenged. They infused parenting with self-consciousness and fevered insecurity. They conscripted teachers into a therapeutic order of education, which meant treating every child as emotionally damaged. They pushed pediatricians to ask kids as young as eight—who had presented with nothing more than a stomachache—whether they felt their parents might be better off without them. In the face of experts’ implacable self-assurance, schools were eager; pediatricians, willing; and parents, unresisting.

Maybe it’s time we offered a little resistance.

One last caveat before we get into it - here’s what I said in my review of Polysecure:

Twin studies tend to show that parenting style has very little effect on anything measurable in adulthood, with variation being about half genetic and half non-shared environment, with very little effect from shared environment (which includes family life and parenting style).

The same applies here. Whatever effect parenting has on adult behavior is dwarfed by genetics and non-shared environment, with some evidence suggesting that genetics cause the lion’s share. The effects described by Shrier are probably real in most circumstances, but ultimately small potatoes compared to the dispositions we’re born with.

Sometimes the Cure is Worse than the Disease

Shrier begins by introducing the term “iatrogenesis,” which she defines as “the phenomenon of a healer harming a patient in the course of treatment.” She describes her own experience with therapy and the iatrogenic effects:

Every week, for a “fifty-minute hour,” my therapist lent me her full attention. If I bored her with my repetition, she never complained. She was a pro. She never made me feel self-absorbed, even when I was. She let me vent. She let me cry. I often left her office feeling that some festering splinter of interpersonal interaction had been eased to the surface and plucked.

She helped me realize that I wasn’t so bad. Most things were someone else’s fault. Actually, many of the people around me were worse than I’d realized! Together, we diagnosed them freely. Who knew so many of my close relatives had narcissistic personality disorder? I found this solar plexus–level comforting. In quick order, my therapist became a really expensive friend, one who agreed with me about almost everything and liked to talk smack about people we (sort of) knew in common.

I’ve never had a therapist, but many people I’m close with have, and this sounds pretty similar to their experiences. There seems to be a certain type of therapist who seems more like a cheerleader than anything else. They ask you what you did over the past week and reassure you that you displayed strength, prudence, and empathy. Any conflict you had was a case of other people being unreasonable. You’d leave with a sense that you were making progress on your mental health despite no actual progress being made.

Shrier goes on to tell a story of how her boyfriend proposed to her, but a month before her wedding, her therapist claimed she wasn’t “ready” to get married and they needed “to do a little more work.” Shrier politely disagreed, stopped therapy, and got (happily, she claims) married. She points out that, as an adult, she was able to disagree with her therapist and make her own choices, but that children in similar situations “are not typically equipped to say these things. The power imbalance between child and therapist is too great.”

Iatrogenesis is a known risk in physical medicine. Every medical procedure carries a risk of mistakes or side effects. The same risk, Shrier argues, applies to mental health care. “ Any intervention potent enough to cure is also powerful enough to hurt.” Therapy can cut off our normal healing process, preventing us from being resilient or moving past things in the natural, intuitive ways.

Therapy can lead a client to understand herself as sick and rearrange her self-understanding around a diagnosis. Therapy can encourage family estrangement—coming to realize that it’s all Mom’s fault and you never want to see her again. Therapy can exacerbate marital stress, compromise a patient’s resilience, render a patient more traumatized, more depressed, and undermine her self-efficacy so she’s less able to turn her life around. Therapy may lead a patient by degrees—sunk into a leather sofa, well-placed tissue box close at hand—to become overly dependent on her therapist.

Shrier points out that even when the symptoms of mental illness get worse, patients assume that therapy has helped. As evidence, she cites a 2003 study about the aftermath of 9/11. New York City was flooded with mental health professionals doing “psychological debriefing” - basically a brief (1-3 hour) session to process a traumatic event. “Although the majority of debriefed survivors describe the experience as helpful, there is no convincing evidence that debriefing reduces the incidence of PTSD, and some controlled studies suggest that it may impede natural recovery from trauma.” Shrier argues that therapy often makes us feel good but has no or a negative effect on our longer term mental health. Therapists themselves often never know because few bother to actually keep track of side effects. Even if they wanted to, there are no actual guidelines for doing so, or even clear guidance on what is “harm” and what isn’t.

Are the Kids Alright?

Gen Z has a lot of issues. According to Shrier, less than half rate their mental health as “good.” 40% have received mental health treatment. One is six children aged 2 to 8 have a diagnosis. 10% have ADHD. Another 10% have an anxiety disorder. Even as the number of therapists and availability of treatment has increased exponentially, the number of problems (including teen suicides) grows and grows. “Teens today so profoundly identify with these diagnoses, they display them in social media profiles, alongside a picture and family name.”

Today’s children are seeing therapists in unprecedented numbers, but are also doing therapy-like things all the time, most notably in schools. They’re set to receive more in the future. In addition to the constantly expanding school counseling staff, tech platforms such as Talkspace openly aspire to provide therapy to every child.

In addition to the official therapy kids are getting, therapy-adjacent concepts have leaked into the culture.

A decade ago, a writer for Slate noted that instead of using moral language to describe misbehavior, educated parents had begun employing therapeutic language. A-list adolescent heroes from Huck Finn to Dylan McKay suddenly struck us as undiagnosed sufferers of “oppositional defiant disorder” or “conduct disorder.” Agency slunk out the back door.

Suddenly, every shy kid had “social anxiety,” or “generalized anxiety disorder.” Every weird or awkward teen was “on the spectrum” or, at least, “spectrumy.” Loners had “depression.” Clumsy kids had “dyspraxia.”

Parents ceased to chide “picky eaters” and instead diagnosed and accommodated the “food avoidant.” (Formal diagnosis: “avoidant restrictive food intake disorder,” or ARFID.) If a kid whined about an itchy tag at the back of his shirt or complained that hallway noise kept him from getting restful sleep, his parents didn’t tell him to ignore it; they bought tag-free clothing of soft Pima cotton and appointed his room with a soft-sound machine to address his “sensory processing issues.” No chiding kids for messy handwriting (that was “dysgraphia”). No telling kids with the blues that it takes time to adjust to a new town or new school (they have “relocation depression”). No reassuring them that it’s normal to miss their friends over the summer (“summer anxiety”).

We’ve all been swimming in therapeutic concepts so long we no longer note the presence of the water. It seems perfectly reasonable to talk about a child’s “trauma” from the death of a pet or the routine humiliation of being picked last for a sports team.

The above passage is an example of Shrier combining her criticisms of therapy culture with her love of weird “tough love” parenting. I get why it’s alarming that shyness is all of a sudden being diagnosed as an anxiety disorder, but what could possibly be the harm in getting rid of an itchy tag or getting a white noise machine to hide hallway noise? What do these things even have to do with each other? The common factor seems to be Shrier’s belief that unless a kid is on fire, the best answer to every problem is “suck it up, Junior.” In this way, the book isn’t really a criticism of therapy so much as it’s a criticism of our modern culture. Shrier seems to believe that we value kids’ happiness and comfort too much, and they would all be better served with authoritarianism and discipline.

Shrier paints a picture of adolescents being kept in perpetual childhood, often into their 30’s. She presents several anecdotes of overrreaching parents managing their children’s schedules, handling their daily tasks, and even one who tracked her daughter’s menstrual cycle. The anecdotes are amusing, though not terribly convincing. There is a real phenomenon, however, of young people doing fewer adult things like driving, working, having sex, and living alone. There could be a lot of explanations for this trend, but overindulgent parents are one plausible factor.

Shrier also points out that liberal parents transfer their own anxieties about the world onto their children, particularly when it comes to climate change. “Climate anxiety” is becoming a common diagnosis as children listen to their parents predict planetary doom and internalize that the future will be a disaster. Meanwhile, rather than reassure their children that things will probably be fine, the most liberal parents “embrace the despair,” believing that anxiety is the mature response to the state of the world. I don’t know how common this is, but it definitely happens.

Therapy for Kids, Though?

I’m a divorce lawyer, so I know a thing or two about bad incentives. The best divorces are the ones that settle early, often without the involvement of a lawyer. If I’m serving my clients well, I urge them to go to mediation, settle quickly, and stay out of court. That also has the side effect of making me much less money. The worst, most acrimonious divorces are the ones that earn their lawyers the most money. We’re all incentivized to encourage our clients to fight like hell over every petty issue.

Therapists have similar incentives. Ideally, a therapist will help someone improve their mental health and discharge them quickly. But their incentives are to encourage their patients to remain lifelong customers. The best therapists rise above these incentives and help their patients get well, but the most successful keep their patients doubting their own mental health and dependent on their therapist for life.

Shrier argues that putting kids in therapy carries the inherent risk of telling them that their parents think something is wrong with them. It also undermines parental authority, though I disagree with Shrier that this is inherently a problem. Some parents ought to be undermined. Therapy carries another inherent risk - telling kids to focus on their feelings.

Placing undue importance on your emotions is a little like stepping onto a swivel chair to reach something on a high shelf. Emotions are likely to skitter out from under you, casters and all. Worse, attending to our feelings often causes them to intensify. Leading kids to focus on their emotions can encourage them to be more emotional.

Shier claims repression is often necessary for a healthy emotional life. Everyone always has something they could be upset about, and asking someone how they’re doing can cause them to focus on it. Our natural tendency toward negativity, Shrier argues, will cause us to focus on whatever negative emotions we’re feeling, amplifying them.

Why? I asked. If all you’re doing is asking, each morning, How are we feeling today, Brayden?, isn’t the child as free to provide a positive answer as a negative one?

That isn’t true, Linden shot back. “Nobody feels great,” he said. “Never, never ever. Sit in the bus and look at the people opposite from you. They don’t look happy. Happiness is not the emotion of the day.”

I’m not sure what to call this view, but let’s just say it’s not my experience. When someone asks me how I’m doing, I tend to focus on positive emotions. I’ve met people that always have something negative to say, but they tend to be pretty unhappy no matter what anyone asks them. I agree with her point, though, that spending an hour focusing on our own internal state is probably not time well spent. Spending an hour catching up with a friend or trying to overcome a challenge would do much more for someone’s mental health.

How to Ruin a Kid in 10 Easy Steps

Shrier’s look into the evidence suggests that there are some pretty well-established ways of improving mental health, and that much of our modern practice does the exact opposite. She finds that most child therapy does what you might recommend if you were trying to raise a generation to be anxious and depressed. Shirer’s bad therapy has ten steps. Getting kids to focus on their feelings is step 1. Step 2 is to induce rumination. Therapists cause us to focus on our worst memories and dwell on them endlessly.

Step 3 is to “Make ‘Happiness’ a Goal but Reward Emotional Suffering”: Shrier claims that having the goal to be happy makes you unhappy. Sounds very Buddhist. She asks us to “consider [our] grandparents.” This is a common theme in the book where Shrier suggests that we should emulate our grandparents because apparently they were paragons of good mental health practices. She tells a story about how her grandmother would be delighted by life’s simple pleasures. “ Each produced in her the spasmodic glee of someone who never expected that her own life would be filled with happiness.” I don’t know about spasmodic glee, but I did have a chuckle at the idea that being excited about a fresh scoop of cream somehow means you expected a life devoid of happiness. Very silly.

The other party of Step 3 (which probably ought to just be Step 4?) is to reward emotional suffering, which I see all the time. The more tragic your backstory, the more attention and sympathy it gets you.

Shrier’s Step 4 is to affirm and accommodate kids’ anxiety. Exposure therapy is proven effective, but often therapists will validate their patients’ fears and encourage them to avoid whatever they are afraid of.

Step 5 is to constantly track and monitor the child. She argues that “adding monitoring to a child’s life is functionally equivalent to adding anxiety.” Stress-free play, the kind kids need for their development, requires privacy, risk, and independence. They can’t get that if adults are always watching.

Step 6 is to diagnose liberally. It makes a difference whether you tell your child that they like to daydream vs. they have ADHD. “A diagnosis is saying that a person does not only have a problem, but is sick.” A diagnosis can demoralize a child or induce learned helplessness.

Step 7 is to medicate. Shrier dedicates a whole chapter to medication, but the issues with overmedication should be obvious. Every psychological medication comes with pretty severe side effects, and should only be taken if absolutely necessary.

Step 8 is to encourage kids to share “trauma.” Shrier quotes a doctor who claims that the best practice when it comes to trauma is to acknowledge it very lightly and then steer the conversation toward the present. Instead, many therapists believe that kids can’t move on until they have “thoroughly examined and disgorged their pain.”

Step 9 is to encourage kids to break contact with “toxic” family. Shrier claims that 30% of Americans 18 and older had cut off contact with a family member (“yeeting the rents,” she calls it). Therapists encourage this by suggesting that all unhappiness in adults is tied to childhood trauma. Once trauma is found, parents are given the blame. This leads children to be deprived of a family support system, and it means grandchildren who believe that they descend from monsters.

Step 10 is to create treatment dependency. Therapists will often cast themselves as the sole pathway toward mental health. Patients start to believe that they are unable to do much of anything alone.

Shrier claims that too much of the bad therapy described above creates emotional hypochondriacs. Honestly, I found this pretty convincing. There are plenty of good therapist that don’t do any of this, but I’ve seen each of these steps get done and the effects it can have.

Blame Canada Smartphones

No appeal to conservative parenting, of course, would be complete without a denouncement of everyone’s favorite punching bag: smartphones. Smartphones are the eternal bogeyman of everyone born before 1994. If you didn’t have a smartphone as a kid, then dadgummit, you know what’s ruining The Kids Today! It’s the consarned phones! Shrier doesn’t bother critically examining any of the actual evidence or trying to tease out the difficult causal questions. What would be the point? It’s common knowledge that phones are the devil and they’re ruining our children’s mental health.

Jonathan Haidt also recently made an attempt to examine youth mental health, and while I haven’t read his book, I’ve listened to a good handful of the approximately 6 billion interviews he’s done about it, and it’s enough to know that he also blames the phones. Of course he does. Everyone blames the phones. Even Zvi blames the phones.

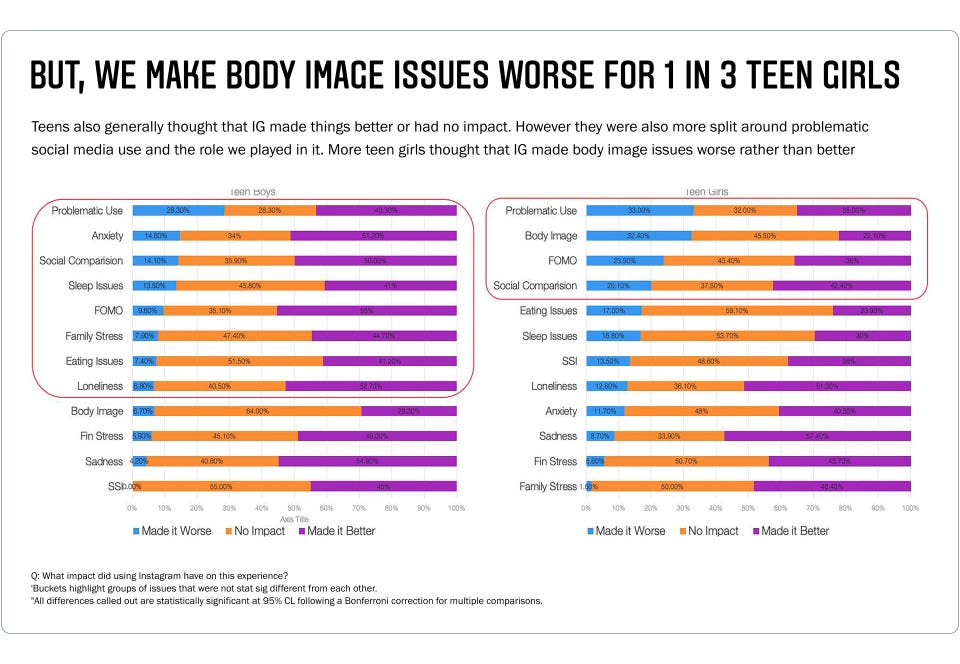

I do not blame the phones. At least, I do not blame the phones directly. High-quality studies of social media use are rare, but the little data available suggests a pretty mixed bag. Most of it suggests that social media’s negative effects on mental health are pretty underwhelming, limited to photo-sharing apps like Instagram, and offset by mental health gains in almost every area. For every kid saying social media makes things worse, there are 2 or 3 saying it’s making things better.

Critics’ main piece of evidence is correlational - teen mental health started getting substantially worse around the time smartphones and social media starting becoming ubiquitous. But aside from this section, Shrier’s whole book is filled with alternative explanations for why child and adolescent mental health is getting worse. The explanation I find most convincing is this one:

This is why I say I don’t directly blame smartphones. The internet, social media, and communications tech is almost certainly related to why kids are spending so much time in isolation. Social media is fun! Kids like it! And when kids like something that’s probably not good for them, the authoritarian impulse is to ban it. So now everyone wants to ban kids from social media. Sure. Lemme know how that works for you.

The focus on phones, of course, ignores the actual biggest problem in kids’ lives: schools.

Educational Malpractice

I’m a harsh critic of American schools, but Shier makes them sound even worse than I’d imagined. According to Shrier, basically every school in the country has instituted an extensive “social-emotional learning” curriculum for “trauma-informed education,” which puts kids in pseudo-therapy from day 1.

Therapists weren’t the only ones practicing bad therapy on kids. Bad therapy had gone airborne. For more than a decade, teachers, counselors, and school psychologists have all been playing shrink, introducing the iatrogenic risks of therapy to schoolkids, a vast and captive population.

Many school days begin with an “emotional check-in,” step 1 to bad therapy. School counseling staff has been greatly expanded, but school counselors have “dual relationships” with children, where they serve as therapist but also school administrator.

Except that school counselors, school psychologists, and social workers enjoy a dual relationship with every kid who comes to see them. They know all a kid’s best friends; they may even treat a few of them with therapy. They know a kid’s parents and their friends’ parents. They know the boy a girl has a crush on, what romantically transpired between them, and how the relationship ended. They know a kid’s teammates and coaches and the teacher who’s giving him a hard time. And they report, not to a kid’s parents, but to the school administration. It’s a wonder we allow these in-school relationships at all.

Shier’s picture of “social-emotional learning” is one in which nosy teachers and administrators are constantly prying into the inner lives and relationships of their students, acting (without proper training) as mental health counselors and also coming between children and their parents. She describes educators who routinely present kids with weird surveys asking about upsetting things, which invite them to ruminate (Step 2) about their worst experiences such as “has someone close to you died?” “have you ever stayed overnight in a hospital?” or “During the past 12 months, did you ever seriously consider attempting suicide?” Not only do these surveys harm children’s mental health, Shrier claims, but they also get stored as part of their permanent record and can be accessed years later. She even interviews Jordan Peterson, who claims that asking kids about suicide makes them preoccupied with it.

If a child can be even informally diagnosed with any kind of learning disability, schools must offer accommodations (Step 4). Instead of motivating children with high expectations, Shier claims, we demoralize them by telling them they need special treatment to perform up to the standards of other students. Some parents will hire “shadows” or “ed techs” to follow their children all day and make sure nothing traumatic happens. Teachers are often prohibited from setting any kind of objective standards and are under constant pressure to made sure nobody ever receives a “bad” grade or is made to feel bad. Even school bullies are treated with “restorative justice” and assigned therapy.

I found the section on schools to be pretty weak tea. It’s reflective of Shrier’s conservative, “tough love” parenting style throughout, constantly suspicious of any educational policy which doesn’t rely on (metaphorically) beating kids into submission. “Social-emotional learning” sounds pretty terrible, but she mostly offers anecdotes, not any hard data about how prevalent the worst abuses are.

I think it’s very likely that schools are a big reason children’s mental health is getting worse, but I don’t think Shrier even comes close to describing the real issues with them. Giving kids some extra time on a test or allowing them to turn in their homework late really doesn’t seem like it should cause big problems. You know what’s actually wrong with schools? Kids hate them. They’re boring. They teach uninteresting, useless things. They were designed to avoid empowering students and foster obedience. They insist that all students proceed at the speed of their slowest classmates. And most of all, kids have no choice but to attend and very little choice about what to do once they get there. If you want to give kids good mental health, they need freedom. They need control over their own lives. They need to feel as though they can make decisions that will actually affect their circumstances or have an impact on the world. Shrier hints at this when talks about how kids need playtime where parents can’t monitor them, but many of her suggestions are to give kids less freedom and more “discipline.” Schools are almost certainly part of the problem, but I don’t think the mental health interventions are the main issue.

To her credit, Shrier also recognizes that kids need independence:

Our kids were doing so much better when they had less—less distraction, less stimulation, less supervision, less intervention, less interference, less accommodation, less parenting. The weight of psychological research demonstrates what kids need most is for their parents (and technology) to stop interrupting, monitoring, curating—diverting them from the organic miracle of growing up.

Shrier speaks approvingly of the “free range kids” movement and 3-year-old Japanese children who are sent alone to buy groceries. Kids need to face actual danger, she says, so they learn how to navigate it. I agree with her! Kids do need freedom! It’s exactly why I disagree with her that kids need discipline. Let kids make their own decisions and deal with the actual consequences, not artificial ones you’ve imposed to teach them a lesson.

Your Body is Not a Scoreboard

Shrier devotes an entire chapter to debunking The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel van der Kolk. I appreciated this chapter because I’ve encountered this idea before and it always struck me as pseudoscientific nonsense. Van der Kolk’s theory is that past trauma is stored in the body, and those “body memories” can trigger PTSD in the present. Often this bodily-stored trauma may be forgotten by the brain, but remembered by the body. With the help of a therapist, such memories could be unearthed and recalled. Another proponent of this idea, Gabor Mate, goes even further:

Not only do we carry the trauma we personally experienced, but we harbor the trauma our parents or ancestors did as well. “Trauma is in most cases multigenerational,” Maté writes. “The chain of transmission goes from parent to child, stretching from the past into the future. We pass on to our offspring what we haven’t resolved in ourselves.”

Shrier points out that the problem with the “body memory” idea is that it’s just a rehash of a previously-debunked theory: repressed memory. In the 1990’s, there was a giant scandal where a number of parents ended up in jail because therapists were able to discover “repressed memories” of abuse from their kids. Van der Kolk himself testified in several repressed memory cases. The convictions were overturned as the theory was largely discredited. It turned out that therapists were simply using the power of suggestion to implant false memories in their patients. I had no idea that The Body Keeps the Score was peddling repressed memory theory, but I’m glad Shrier took the time to push back against it.

Shrier’s Crusade Against Gentle Parenting

Chapter 9 of Bad Therapy is all about Shrier’s theory that “gentle parenting” - any parenting style that isn’t based on authoritarianism and harsh discipline - is ruining kids’ mental health. Shrier dreams of a more “masculine” style of parenting, like back in the good old days, where kids were spanked, parents yelled, and nobody felt pressured to attend every soccer game. Parents today, according to Shrier, are too soft, and concern themselves far too much with their children’s well-being. Shrier counsels a parenting style she calls “knock it off, shake it off” parenting.

The sort that met kids’ interpersonal conflict with “Work it out yourselves,” and greeted kids’ mishaps with “You’ll live.” A loving but stolid insistence that young children get back on the horse and carry on.

“Knock it off” didn’t suffice in the face of all misbehavior. But in the main, it put the onus on kids to figure out what was wrong with their conduct and desist. “Knock it off” didn’t overexplain: It credited kids with common sense or nudged them to develop it. Rules had exceptions and workarounds, but “knock it off” signaled a parent’s disinclination to become entangled in them. Every kid who hopes to hold down a job without making himself a terrible (and disposable) burden to an employer needed to master this art of following simple instruction—without seven hundred time-consuming follow-up questions. “Knock it off” meant: You’re a smart kid, figure it out. But also: You can.

“Shake it off” didn’t solve the worst injuries, of course, but that was never its purpose. (No one except a sadist ever thought a child could run on a broken leg.) And it rarely operated alone: the other parent, the gentler one, often cushioned its impact. But “shake it off” did a helluva job playing triage nurse to kids’ minor heartaches and injuries, proving to kids that the hurt or fear or possibility of failure need not overwhelm them. “Shake it off” provided its own kind of tough love and emotional nourishment. It taught kids to soldier into a world with the hopeful disregard of danger that a cynic might term naivete. Others call it courage.

I actually agree with most of this prescription. Kids are far more capable than we tend to credit them. With my four-year-old, I almost never intervene in a conflict unless she asks, and my usual advice is to tell the other kids how she feels. The difference is that I validate her feelings and let her decide how to proceed. Part of respecting that kids are capable means respecting their ability to make their own decisions. If she wants to “get back on the horse and carry on,” that’s fine. But it’s also fine if she doesn’t. That’s her decision.

With injuries, I find there’s very little for me to do most of the time. I do think it would be harmful if I fussed over every bruise or scrape, insisted on applying Neosporin and bandages, or projected out my own anxiety about her getting hurt. But it would be equally harmful to withhold affection and downplay the very real pain that she’s in. The important part is that I follow her lead when deciding how serious to treat something. If it’s serious to her, it’s serious to me, but I make sure to never (implicitly or otherwise) encourage her to think a minor injury is more of a big deal than it is.

Shrier has a good point about parents who seek to impose “consequences” rather than punishments:

Where things get a little murky is when the “consequences” aren’t actually consequences. They’re punishments in dress-up. “Since you threw your food on the floor, I cannot take you to the park. I cannot take anyone to the park who throws their food on the floor, because now I have to spend the time I would have spent at the park cleaning this up. Would you like to help clean it up?” This is supposed to impress the child because after all, the parent has avoided appealing to her own authority. She merely offers description of what happened, non-hierarchical invitation to “connect” over the new task, and so much shrugging of shoulders: “I don’t make the rules here! I just follow them.”

But of course, it’s also bollocks. A parent can take a kid to the park who has thrown his food on the floor. She just doesn’t want to. And she does make the rules—or, at least, she’s chosen to adopt the rules, supplied by the parenting experts. But here is the parent straining to act as therapist, divesting herself of moral judgment, refusing to chide bad behavior,

One of things that makes parenting easier is remembering what it’s like to be a kid, and nothing made me angrier than being lied to. Particularly enraging were lies about adults doing things that were clearly for their benefit and claiming it was for mine. Kids can tell the difference, and they can tell the difference between consequences and punishments. The thing is, you don’t need to do that. You can just do what you want and be honest about it. If your kid is throwing a tantrum and it makes you want to skip your park trip, you can just say that. It’s not a punishment if it’s genuinely how you feel. The point is just to be honest that it’s about you and what you want.

Shrier has contempt for so-called parenting experts who counsel parents to empathize with their children, seek to be nonjudgmental, and avoid punishments. This “gentle parenting,” she claims, turns children into monsters. They learn that there are no consequences for misbehavior and that acting out is the best way to get what they want. Effort to accommodate our children’s sensitivities just ends up creating more sensitivities. According to Shrier, gentle parenting just creates entitlement.

In Shrier’s conception, the most important quality a parent possesses is authority. A parent must be in charge. Disobedience must be punished (preferably by spanking). A parent’s affection and high regard should be contingent upon good behavior. Children’s anxieties and challenges should largely be ignored. Their preferences should be steamrolled. They should have little input into major life decisions.

What a crock of shit. It’s easy to point and laugh at the most ridiculous excesses of unreasonably permissive parents, but Shrier’s purported “spare the rod, spoil the child” wisdom is anything but. Throughout the book, Shrier is conflating two very different things: Having authority and having boundaries.

Parents inherently have authority. There’s no way around it. If I don’t take my child to the park, she’s not going. If I don’t get her a snack, she’s not eating. She can’t even open most doors without me. She’s just not capable of doing most things herself yet. Her mom’s and my level of control over her life starts out nearly absolute, and ideally gets smaller and smaller over time. There is no need to assert our authority. It’s a fact of life.

The way to prevent a kid from feeling entitled is to have boundaries. The way to not get pushed around by your kids is just to… not get pushed around by your kids. Do what you want. Don’t be a doormat. Value your child’s needs, but make sure you keep your own (and other people’s) needs on the same level. If you do that, you don’t need to punish anyone. Imposing arbitrary punishments does little to teach kids anything other than to resent the authority imposing them. Hitting them might get them to comply, but it won’t teach them why they should trust you. The only way to do that is to be trustworthy. If you tell kids the truth, they’ll believe you. If you treat their preference as though they matter, but they don’t outweigh everyone else’s, they’ll believe that too.

The funny thing about this is it’s the exact same advice I have for dealing with adults. Healthy boundaries are the key to every good relationship. Any relationship can become toxic if one party is being overbearing and handling the other’s responsibilities. The difference with kids is that they’re actually dependent, so there’s a lot more they need you to do for them. Good parenting recognizes, above all, that children are people and have the same need for dignity and autonomy that adults do. Shrier is right to skewer parents who are unable to set boundaries, but she’s way off when she insists on obedience and punishments. Strong boundaries are enough to get the job done.

I also disagree with Shrier’s take that kids need to suffer in order to become functional adults. I run into this attitude all the time, exemplified by Calvin’s dad:

Shrier shares Calvin’s dad’s attitude that growing up means “building character” by being miserable. I’m always baffled by this view. I don’t know a single person, no matter how privileged, whose problem is that they haven’t suffered enough. Nobody’s life is perfect. Nobody has everything they want. The problem with the world is that people suffer too much, not too little.

This attitude also relies on the idea that certain skills such as resilience need to be developed in childhood or else the “critical window” is missed and they can never be learned. Even the best evidence for this idea is weak. My experience is that people develop skills when they need them. If someone manages to get through childhood without needing to face adversity, as unlikely as that would be, I would call it a miracle. The first time something really bad happens, they wouldn’t be equipped to deal with it, but that’s the same situation kids are in the first time something bad happens to them. It’s likely that adults are more able to develop that skill than children. There’s no need to add adversity to our children’s lives. They’ll face plenty eventually.

Verdict: Not Recommended

Bad Therapy isn’t all bad. It makes good points about the uselessness and counterproductivity of many types of therapy, and the advancement of therapy-like practices into our children’s lives, as well as children’s need for freedom and independence. Unfortunately, it’s mixed in with some really questionable childrearing recommendations that ultimately undermine the message. I don’t recommend it.