Seriously, Stop Telling Fat People to be Thin

Previously: Stop Telling Fat People to be Thin, Bill Maher is Wrong About Fat Shaming

Doctors tend to prescribe weight loss for a wide range of medical issues (or no issues at all other than "unhealthy weight"). But there is very little evidence that weight loss, on its own, results in better health outcomes, and some evidence that weight loss may even increase one's mortality risk. Rather than prescribing weight loss, doctors should directly recommend behaviors - eating healthy and exercising - which are shown to improve health regardless of whether they cause a change in body size.

Correlation is not Causation

Most of the reason for the assumption that weight loss is healthy is the fact that obesity is correlated with certain health conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and other life-threatening illnesses. Many sources, including doctors, view this correlation and conclude that obesity is the cause of these conditions and recommend weight loss to mitigate them. However, there are reasons to doubt this naïve view of causation.

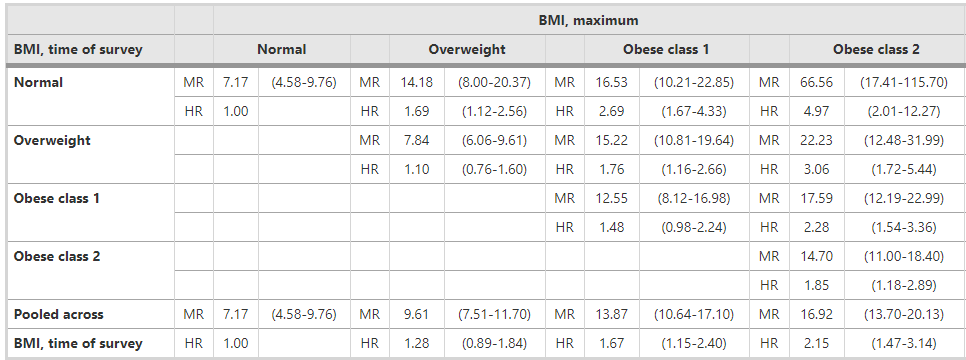

Judging by simple correlation, obesity by itself is harmful, but weight loss is counterproductive. As I discussed in a previous post, a study published in Population Health Metrics pulled data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (1988-1994 and 1999-2004) and linked it to the National Death Index through 2006 to calculate Mortality Rates (MR) and Hazard Ratios (HR) for people in different BMI classes and different maximum BMI classes. They are both measurements of how likely a person is to die (from any cause). A higher number means you're more likely to die.

A person with a maximum BMI of "Obese" but a current BMI of "normal" is someone who at one point was obese, but lost weight and is now a normal weight. So by comparing obese people to formerly obese people, we can observe the effects of weight loss on all-cause mortality. The results are shown in this table:

The bottom of each column are the numbers of people who are currently at their maximum BMI. As you move up the columns, you see the numbers for people who have lost weight.

Looking at the final column, a person in "obese class 2" has a MR of 14.70. A person who used to be in obese class 2, but has lost weight and is now in obese class 1 has a MR of 17.59, nearly three points higher. Dropping down to "overweight" raises their MR to 22.23, and dropping to "normal" weight raises it to a whopping 66.56. This pattern holds for all weight classes, regardless of whether you measure MR or HR (except, curiously, going from obese class 1 to overweight, measuring by MR). Losing weight is strongly correlated with all-cause mortality.

Of course, these are just raw numbers that show a correlation. They don't mean that losing weight is the cause of the increased chance of death. Both factors could be caused by a third common factor. In particular, studies have found that when weight loss is separated into intentional and unintentional categories, intentional weight loss has no health effects while unintentional weight loss is highly correlated with negative outcomes. Other studies have suggested that "reverse causation" (i.e. weight loss caused by disease) is the reason for these numbers. This does, however, disprove the naïve correlation hypothesis. By pure correlation, weight loss is associated with a dramatic increase in all-cause mortality.

Intentional Weight Loss Probably Has No Effect on Health

The evidence on this point is mixed, but most studies suggest that intentional weight loss has very little effect on a person's health.

A 2013 meta-analysis examined 21 studies, which all included randomized controlled trials with a non-diet group, an explicit goal of weight loss, and follow-up of at least 2 years. It found "no clear relationship" between losing weight and health outcomes.

Changes in diastolic and systolic blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels were small, and none of these correlated with weight change. There were also very small effects of these diets on lipid-lowering medication use and coronary morbidity and mortality. There were a few larger positive effects for hypertension and diabetes medication use, as well as diabetes and stroke incidence. In correlational analyses, however, we uncovered no clear relationship between weight loss and health outcomes related to hypertension, diabetes, or cholesterol, calling into question whether weight change per se had any causal role in the few effects of the diets. Increased exercise, healthier eating, engagement with the health care system, and social support may have played a role instead.

Similarly, a 2004 study on diabetics found that weight loss was correlated with a substantial increase in mortality, but that this was entirely accounted for by unintentional weight loss. Interestingly, the study found that those who merely attempted to lose weight had better health outcomes, regardless of whether any weight was actually lost.

Healthy Habits Improve Health Independent of Body Size

The two studies noted above both found substantial benefits of healthy lifestyle habits such as "increased exercise, healthier eating, engagement with the health care system, and social support." In particular, the seeming paradox in the diabetic study is explainable by the fact that people who attempted weight loss would have engaged in healthy lifestyle interventions which are beneficial in themselves regardless of whether they resulted in weight loss.

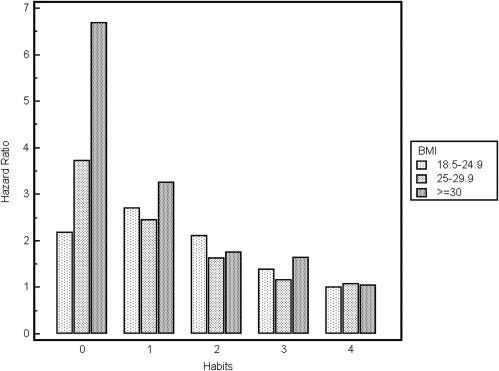

A 2012 study confronted this question directly. It reviewed survey data to determine how beneficial healthy lifestyle habits were to people in different BMI categories. The habits examined were "eating 5 or more fruits and vegetables daily, exercising regularly, consuming alcohol in moderation, and not smoking." Among people who had no healthy habits, higher BMI was associated with worse health (as expected), but as soon as one healthy habit was added, the correlation disappeared. The graph is striking:

So it seems that excess weight is a problem if you smoke, drink excessively, avoid fruits and vegetables, and don't exercise, but is otherwise fine. A 2016 study analyzed survey data on health professionals and found similar results. Very high weights showed slightly worse outcomes, though the error bars were large and the data could have been skewed by surveying only healthcare professionals. As noted above, other studies have listed "engagement with the healthcare system" as impactful on health outcomes.

I would like to see an analysis that is focused only on diet and exercise, as I suspect that drinking and (especially) smoking confuse the data more than they illuminate, but so far I have been unable to fine such a study. Eating less by itself has been demonstrated to improve outcomes by studying bariatric surgery patients. In the linked study, obese participants who underwent bariatric surgery (which forces people to eat less by constricting their stomachs) caused both better health outcomes and weight loss. However, as in previous studies, the amount of weight lost was uncorrelated with health outcomes (though the authors admitted that the study was "not powered to compare types of intervention or different degrees of weight loss within the surgery group." Disappointing).

Focusing on Weight Is Bad for Your Health

Typically, weight loss strategies involve some combination of healthy eating and exercise. However, these strategies often fail to lead to substantial weight loss, which cause people to abandon them. This is unfortunate because healthy eating and exercise are beneficial regardless of whether they lead to weight loss. Focusing only on the weight loss component can undermine one's motivation to continue with habits that could be the difference between life and death.

A 2014 study reviewed whether "weight inclusive" (focus on healthy habits instead of weight loss) or "weight normative" (focus on weight loss) approaches worked better for improving obese people's health.

while directing efforts toward improving health access and reducing weight stigma). Data reveal that the weight-normative approach is not effective for most people because of high rates of weight regain and cycling from weight loss interventions, which are linked to adverse health and well-being. Its predominant focus on weight may also foster stigma in health care and society, and data show that weight stigma is also linked to adverse health and well-being. In contrast, data support a weight-inclusive approach

Data tends to show that a Health at Every Size (HAES) approach works better. HAES is a movement to promote healthy habits regardless of body size.

Doctors Should Prescribe Healthy Habits, Not Weight Loss

All of the data I've been able to find is consistent with the idea that high BMI and poor health are caused by a common factor - poor diet and lack of exercise - and that's why they are correlated. But regardless, once a person is obese, the evidence I've been able to find suggests that encouraging such people to lose weight is counterproductive, and medical interventions should focus on healthy habits, including a healthy diet and regular exercise. Engaging in healthy habits can mitigate or eliminate all supposed negative health effects of obesity, and also helps to destigmatize a low-status population.

Also, speaking as someone whose BMI varied from "normal" to "obese" at different times in my life, I promise that nearly every obese person has already been told to lose weight. If that's your advice, it's probably not novel or helpful. On the other hand, many people haven't heard of Health at Every Size, and may be unaware that they can be just as healthy (or healthier) than a thin person if they engage in healthy lifestyle habits. It's much better advice.