The Postrat Gospel - a review of Cat’s Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut

This was originally written for the Astral Codex Ten book review contest, and has been reproduced here now that the finalists have been announced

Kurt Vonnegut is difficult to classify. He’s often described as a science fiction writer, but that never struck me as accurate. Many of his stories involve the future or advanced technology, but those elements seem to be afterthoughts in his stories which are actually about mundane human struggles. His novels could plausibly be described as works of philosophy, but what novel couldn’t? What I’ve realized is that Vonnegut is a science fiction writer, but the speculative technology he writes about isn’t mechanical or digital. Vonnegut writes about social technology, and much of the time he really nails it.

The hardest part of this review was about picking which Vonnegut novel to cover. I considered his 1952 novel about humanity’s angst at being replaced by AI (Player Piano), his 1959 novel lampooning wokeness and its obsession with privilege (The Sirens of Titan), or his 1962 novel about the dangers of trolling too hard (Mother Night).

I settled on Cat’s Cradle, Vonnegut’s 1963 novel about postrationalism. Like most of his other novels, the actual story isn’t the point, but rather serves as a scaffold to bring out the true meaning of the novel - in this case the religion Bokononism.

A Short History of the Apocalypse

The story of Cat’s Cradle follows a first-person narrator. He is a typical Vonnegut protagonist in that he is an everyman who, if anything, is less virtuous and less interesting than the other characters featured. Above all, Vonnegut protagonists tend not to exercise agency and simply respond to events in an often foolish but profoundly ordinary way, and our narrator is no exception.

The novel immediately breaks one of my cardinal rules for fiction, which is that it’s about a writer. Generally, I recommend avoiding stories where writers write about writers, but Vonnegut is an exception because his protagonists barely matter. In Cat’s Cradle, the narrator is writing a book about Felix Hoenikker, a co-creator of the atomic bomb, which leads him to travel to the small and extremely poor Caribbean island nation of San Lorenzo to meet with Hoenikker’s son Frank.

Frank Hoenikker is the bodyguard and named successor to the president of San Lorenzo “Papa” Monzano. Papa Monzano is ill from cancer and will likely die soon. Frank, it turns out, is not interested in taking over the presidency and offers the narrator the job. He is somewhat reluctant, but accepts after being told that it will involve marrying Mona, Papa Monzano’s adopted daughter and the most beautiful woman he has ever seen.

Unbeknownst to our narrator, Felix Hoenikker invented a substance called ice-nine, which is a type of water molecule whose freezing point is 114.4 degrees Fahrenheit, and has the unfortunate and apocalyptic effect of converting all other water molecules it touches into ice-nine. Felix Hoenikker’s three children discovered a chunk of ice-nine after their father’s death and divided it up between the three of them. Each child used their possession of ice-nine for personal gain, including Frank who secured his position with Papa Monzano by giving him a piece of it.

Rather than suffer through his cancer, Papa Monzano commits suicide by eating his piece of ice-nine. It immediately turns all of the water in his body to ice. Then during the inauguration ceremony for the new president, a fighter jet malfunctions and crashes into the palace, causing Papa Monzano’s body to fall into the ocean. All of the water connected to the ocean turns to ice, dooming all life on Earth.

The Birth of Bokonon

“Bokonon” was formerly known as Lionel Boyd Johnson. Originally from Tobago, Johnson sailed alone to London in search of education. His economics study was cut short by WWI, where he fought for the British. After being injured and discharged, his return trip home was interrupted by a series of events worthy of Odysseus which eventually landed him in New Bedford, Massachusetts. It was around this time that he “developed a conviction that something was trying to get him somewhere for some reason.” He eventually accepted a position as a first mate on a ship traveling the world which ended up shipwrecked in India. There, he became a follower of Mohandas Gandhi and was deported for leading groups resisting British rule. He was sent home to Tobago where he built himself another ship and sailed around the Caribbean hoping for a storm to blow him to his destiny. A storm did eventually form and chased Johnson to Haiti where he met a deserter from the U.S. Marines named Earl McCabe. McCabe hired Johnson to sail him to Miami, but on the way they were shipwrecked and washed ashore, naked, on San Lorenzo.

Much of Bokononism takes the form of poems called “Calypsos.” Johnson wrote this about his experience:

A fish pitched up

By the angry sea

I gasped on land

And I became me.

Johnson - now “Bokonon” as his name was pronounced in the San Lorenzan dialect - and McCabe discovered that San Lorenzo was one of the most miserable places on the planet. It had no strategic positioning, no natural resources, no rich soil, and nothing of value to anyone. Before their arrival, the country existed in a state of mostly anarchy except that the Castle Sugar corporation barely broke even by enslaving part of the population and earning just enough to pay the slave drivers. “When McCabe and Johnson arrived in 1922 and announced that they were placing themselves in charge, Castle Sugar withdrew flaccidly, as though from a queasy dream.”

Bokonon and McCabe set out to turn the country into a utopia. Bokonon wrote later about the topic of utopias:

The hand that stocks the drug stores rules the world.

Let us start our Republic with a chain of drug stores, a chain of grocery stores, a chain of gas chambers, and a national game. After that, we can write our Constitution.

McCabe unsuccessfully tried to design a functional government while Bokonon invented a new religion.

When it became evident that no governmental or economic reform was going to make the people much less miserable, the religion became the one real instrument of hope. Truth was the enemy of the people, because the truth was so terrible, so Bokonon made it his business to provide the people with better and better lies.

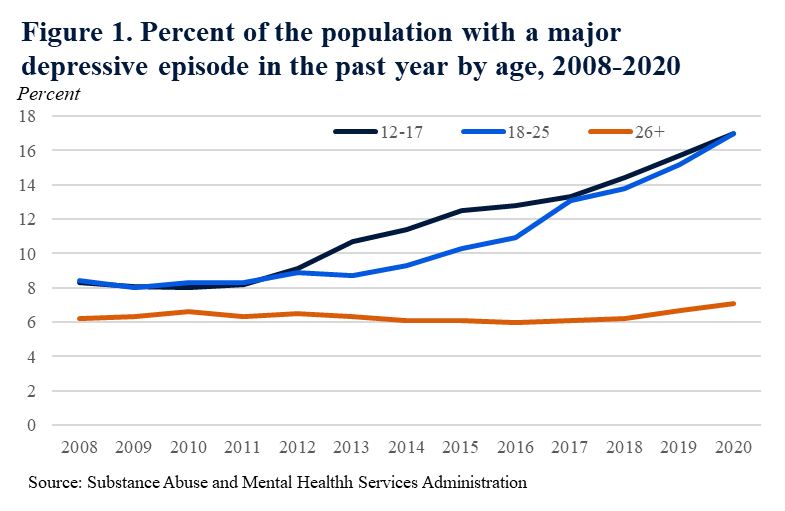

The parallels to the contemporary world write themselves. 90% of Americans feel that we are in a “mental health crisis” and things aren’t much better internationally. On the latest ACX survey, over 30% reported probably having depression and another nearly 30% reported having anxiety. Even as the world grows in prosperity and life expectancy, our mental health is taking a nosedive. Economic and governmental reforms have failed. The world cries out for a better way of thinking.

Bokonon asked McCabe to outlaw his religion to give it “more zest.” So anyone caught practicing Bokononism was sentenced to death by “the hook,” which is exactly what it sounds like. As of the writing of the novel, Bokononism was still outlawed despite everyone on San Lorenzo, including Papa Monzano, being a devout Bokononist.

"Papa" Monzano, he's so very bad,

But without bad "Papa" I would be so sad;

Because without "Papa's" badness,

Tell me, if you would,

How could wicked old Bokonon

Ever, ever look good?

Or, in modern parlance:

In that spirit, I propose that discussions of Bokononism be banned in ACX comments, the subreddit, the Discord server, and Lesswrong. The real dream is to get the CDC to officially denounce it as “misinformation” and pressure social media companies to censor it.

Isn’t it Ironic?

Though Cat’s Cradle was published in 1963, Bokononism is a religion made for the modern world. And the modern world is in need! Belief in traditional religions has been falling dramatically, but rather than religion fading into the background, a new secular religion has arisen to take their place, often with devastating effects. The main problem with religions - old and new - is that they are lies but they claim to be true. People fight, kill, and inflict untold suffering out of faith in the truth of their comforting falsehoods. Bokonism, on the other hand, is explicitly false. The title page of the First Book of Bokonon consists of a warning: “Don't be a fool! Close this book at once! It is nothing but foma!” The narrator helpfully adds: “foma, of course, are lies.” It has a built-in defense against ever taking it too seriously.

Bokononism is perfect for the online world because the internet runs on irony and Bokononism has irony at its core. LARPing a belief system that you know is fake so hard that you forget it’s fake but still maintain plausible deniability is a pretty good description of most internet subcultures I know of. Bokononism fits in perfectly with the terminally online.

The remainder of the first book, as far as we are shown, is as follows:

All of the true things that I am about to tell you are shameless lies.

In the beginning, God created the earth, and he looked upon it in His cosmic loneliness.

And God said, "Let Us make living creatures out of mud, so the mud can see what We have done." And God created every living creature that now moveth, and one was man. Mud as man alone could speak. God leaned close as mud as man sat up, looked around, and spoke. Man blinked. "What is the purpose of all this?" he asked politely.

"Everything must have a purpose?" asked God.

"Certainly," said man.

"Then I leave it to you to think of one for all this," said God.

And He went away.

The only other verse from the first book that we are shown is Bokonon’s commandment: “Live by the foma that make you brave and kind and healthy and happy.” If that sounds familiar to you, it’s probably because that’s the implicit message of postrationalism.

A Postrationalist Religion

“What is postrationalism” is not a question with an easy answer. ChatGPT calls it:

a perspective or approach that acknowledges the limitations of traditional rationalism, particularly its focus on explicit, systematic reasoning. It integrates intuition, emotions, and other forms of understanding that are not purely logical or analytical. Postrationalists argue that rationality should include not only formal logic and evidence-based reasoning but also the subconscious, the intuitive, and the experiential aspects of human cognition. They emphasize that our understanding and decision-making processes are often more complex and less transparent than rationalist models suggest, advocating for a broader, more flexible approach to thinking and problem-solving.

Seems a little academic to me for a subculture largely existing on Twitter. My experience of the postrat scene suggests that the defining feature is that while rationalists believe that the path to a better and more meaningful life involves making our maps match the territory as much as possible, postrats are self-awarely willing to believe in things that aren’t true if they find it makes their lives better. The Bokononist belief in foma is why Obvious Nonsense like astrology, acupuncture, crystal healing, tarot, etc. are ubiquitous within the scene. It’s not that they’ve critically studied the evidence and intellectually believe these things are true. It’s that their lives are better when they believe in them.

For instance, here is a quintessential postrationalist declaring that he only believes in true things, except of course for fairies and elves:

When I was first on the scene, it was baffling to me that someone would declare a belief in something but at the same time acknowledge its falsehood, but I understand it now as part of an intentionally chosen ironic stance toward the world. It’s not a delusion so much as it’s a person choosing to live by the foma that makes him the person he wants to be. It sounds foolish to me but I have that in common with Bokonon, who “always said he would never take his own advice, because he knew it was worthless.”

That’s not to say that the Books of Bokonon contain no wisdom. To the contrary, they contain many profound truths. For instance, the title of the Fourteenth Book of Bokonon is “What Can a Thoughtful Man Hope for Mankind on Earth, Given the Experience of the Past Million Years?” There is only one verse, and it consists of a single word: “Nothing.” What religion or philosophy has more wisdom to offer than this?

Still not convinced? Consider Bokonon’s verse on the ignorance of learned men:

Beware of the man who works hard to learn something, learns it, and finds himself no wiser than before. He is full of murderous resentment of people who are ignorant without having come by their ignorance the hard way.

Is that not, as The Kids would say, a banger tweet? It’s even under 280 characters.

The Karass and the Granfalloon

Bokononists believe that humanity is divided into teams to unknowingly do God’s will. Each team is called a karass. Bokonon says “If you find your life tangled up with somebody else's life for no very logical reasons that person may be a member of your karass.” In particular, Bokonon advises his followers not to resist when it feels like they are being called somewhere. “Peculiar travel suggestions are dancing lessons from god.”

If a karass is a wheel, the hub is the wampeter. A wampeter is the Macguffin of your karass. It can be anything so long as the members of the karass form a “spiritual orbit” around it. Wampeters are temporary. At any given time, a karass will have two wampeters, one growing in importance and one falling. A wampeter is different from a kan-kan, which is what draws you in to your karass. Our narrator suspects that the book he is writing is his kan-kan and his wampeter is the cataclysmic substance ice-nine.

We may be able to identify certain members of our karass or one of our wampeters at any given time, though we will inevitably fail to see the extent of them. Bokonon admonishes that “anyone who thinks he sees what God is Doing” is a fool. When Bokononists think of how complicated and unpredictable everything is, rather than attempt to understand, they simply whisper “busy busy busy.”

Tiger got to hunt,

Bird got to fly;

Man got to sit and wonder, "Why, why, why?"

Tiger got to sleep,

Bird got to land;

Man got to tell himself he understand

Anyone can be a member of your karass, and it follows no rules. Bokonon writes:

Oh, a sleeping drunkard

up in Central Park,

And a lion-hunter

In the jungle dark,

And a Chinese dentist,

And a British queen--

All fit together

In the same machine.Nice, nice, very nice;

Nice, nice, very nice;

Nice, nice, very nice--

So many different people

In the same device.

Occasionally, God creates a karass of two, known as a duprass. You can recognize them by your burning envy at how satisfied they seem with each other. “A true duprass,” Bokonon writes, “can’t be invaded, not even by children born of such a union.” Members of a duprass always die within a week of each other.

Sometimes, people will mistakenly think a man-made category is a karass. That is not how God gets things done. Bokonon calls this a granfalloon, or a false karass. Classic granfalloons are “the Communist party, the Daughters of the American Revolution, the General Electric Company, the International Order of Odd Fellows—and any nation, anytime, anywhere.”

If you wish to study a granfalloon

Just remove the skin of a toy balloon.

That mental health crisis we were discussing earlier? Many believe it is due to the atomization of modern society. The Surgeon General has declared a “loneliness epidemic.” People are more disconnected from each other than ever and our old granfalloons aren’t working to keep us together. People crave new ways of connecting and forming communities. Most of the people I know of who are successful at creating communities are doing so by coalescing around a wampeter. To take it back to the postrats, the most successful community-building exercise I’ve seen in years is Vibecamp, an example of a kan-kan if I’ve ever seen one. Many reading this likely have a spiritual orbit about the Astral Codex Ten blog or LessWrong. The OG rats are creating their own kan-kan with LessOnline. What is the point of any of this if not to draw together one’s karass? Do you feel compelled to attend the next one? Then perhaps these are your dancing lessons from God.

A savvy reader might object here. Isn’t rationalism a classic granfalloon? It is, of course, if you see your fellow rationalists as your karass. But the point of these gatherings is not to engage in a feeling of connection over a shared identity. Rather, the point is to make yourself visible so the members of your karass can gravitate toward each other. The actual groups that form tend to be rather small and brought together by shared purpose. Often, these events lead to the birth of several new wampeters which begin to rise in importance.

“Universal Love” said Bokonon

Bokononists believe that it is impossible to put your feet sole-to-sole with another person and not love them (“provided the feet of both persons are clean and nicely tended”). This ritual is called boko-maru, or the mingling of awareness. It is Bokononism’s most spiritual practice.

We will touch our feet, yes,

Yes, for all we’re worth,

And we will love each other, yes,

Yes, like we love our Mother Earth.

That is Bokonon’s Calypso on boko-maru. Here is our narrator’s response upon trying it for the first time with his soon-to-be bride Mona:

Sweet wraith,

Invisible mist of …

I am—

My soul—

Wraith lovesick o’erlong,

O’erlong alone:

Wouldst another sweet soul meet?

Long have I

Advised thee ill

As to where two souls

Might tryst.

My soles, my soles!

My soul, my soul,

Go there,

Sweet soul;

Be kissed.

Mmmmmmm.

Sounds nice!

Bokononists are encouraged to mingle their awareness with anyone they please. Upon learning this, the narrator becomes upset:

“Is—is there anyone else in your life?”

She was puzzled. “Many,” she said at last.

“That you love?”

“I love everyone.”

“As—as much as me?”

“Yes.” She seemed to have no idea that this might bother me.

I got off the floor, sat in a chair, and started putting my shoes and socks back on.

“I suppose you—you perform—you do what we just did with—with other people?”

“Boko-maru?”

“Boko-maru.”

“Of course.”

“I don’t want you to do it with anybody but me from now on,” I declared.

Tears filled her eyes. She adored her promiscuity; was angered that I should try to make her feel shame. “I make people happy. Love is good, not bad.”

“As your husband, I’ll want all your love for myself.”

She stared at me with widening eyes. “A sin-wat!”

“What was that?”

“A sin-wat!” she cried. “A man who wants all of somebody’s love. That’s very bad.”

Bokonon preaches that it’s wrong “not to love everyone exactly the same.” This is probably the most difficult part of Bokononism. Who could possibly love everyone the same? Bokonon, of course, would probably call you wise for objecting to what he says. I choose to view it as aspirational. We can’t actually love everyone the same, but we can always strive to love each other more than we do. And most of us could probably stand to be less of a sin-wat.

The narrator quickly comes around and converts to Bokononism, accepting Mona’s libertine ways. After the apocalypse, when the narrator struggles with whether to remember Mona as sublimely spiritual or as a dazed cult addict, he remembers Bokonon’s Calypso about love:

A lover's a liar,

To himself he lies,

The truthful are loveless,

Like oysters their eyes!

Truthfully, who among us hasn’t indulged in a bit of foma about the people we love? Ultimately, does love not require it?

The End of the World

Bokonism also has wisdom for the end times, largely because Bokonon lived through them. The Books of Bokonon include the concept of pool-pah, alternately translated in some places as “wrath of god” and in others as “shit storm.” As it happened (“as it was meant to happen,” Bokonon would say), after ice-nine froze the oceans, our narrator and Mona survived thanks to an underground bunker. They emerged after a few days to find that a new Calypso was written in the ruins:

Someday, someday, this crazy world will have to end,

And our God will take things back that He to us did lend.

And if, on that sad day, you want to scold our God,

Why just go ahead and scold Him. He'll just smile and nod.

Continuing on, they discovered that thousands of San Lorenzens had survived the initial chaos, gathered in a large circle, and each pressed a bit of ice-nine to their lips, freezing them instantly. A note was under a boulder nearby:

To whom it may concern: These people around you are almost all of the survivors on San Lorenzo of the winds that followed the freezing of the sea. These people made a captive of the spurious holy man named Bokonon. They brought him here, placed him at their center, and commanded him to tell them exactly what God Almighty was up to and what they should now do. The mountebank told them that God was surely trying to kill them, possibly because He was through with them, and that they should have the good manners to die. This, as you can see, they did.

The note bore Bokonon’s signature, though he was nowhere to be found. Mona, ever the true believer, took Bokonon’s advice and pressed a chip of ice-nine to her own lips.

The novel ends with the narrator finding Bokonon sitting on a rock, contemplating the final verse for the Books of Bokonon. He decides to end with this:

If I were a younger man, I would write a history of human stupidity; and I would climb to the top of Mount McCabe and lie down on my back with my history for a pillow; and I would take from the ground some of the blue-white poison that makes statues of men; and I would make a statue of myself, lying on my back, grinning horribly, and thumbing my nose at You Know Who.

There are many in our communities who anticipate a large amount of pool-pah in the near future. Some even believe that we are living through the end times. This understandably causes some existential angst. Even those who don’t see doom in our future aren’t necessarily doing great. As Bokonon says, “maturity is a bitter disappointment for which no remedy exists, unless laughter can be said to remedy anything.” If you are one of these people, I say to you: consider converting to Bokononism. If laughter is the remedy, why not have a religion that’s already a joke? The fact that none of it is true doesn’t need to make it any less comforting. Everyone believes in foma of one variety or another, and your duty is only to believe the type that makes you brave and kind and healthy and happy. The fact that it’s untrue is an advantage because you’ll know not to get all up your own ass about it.

Or don’t. It’s not as if it matters!

I will leave you now with the last rites of the Bokononist faith, which you can say any time you feel afraid of death. All you need is a friend to say it to you, and you repeat each line, preferably with the soles of your feet touching:

God made mud.

God got lonesome.

So God said to some of the mud, "Sit up!"

"See all I've made," said God, "the hills, the sea, the sky, the stars."

And I was some of the mud that got to sit up and look around.

Lucky me, lucky mud.

I, mud, sat up and saw what a nice job God had done.

Nice going, God.

Nobody but you could have done it, God! I certainly couldn't have.

I feel very unimportant compared to You.

The only way I can feel the least bit important is to think of all the mud that didn't even get to sit up and look around.

I got so much, and most mud got so little.

Thank you for the honor!

Now mud lies down again and goes to sleep.

What memories for mud to have!

What interesting other kinds of sitting-up mud I met!

I loved everything I saw!

Good night.

I will go to heaven now.

I can hardly wait...

To find out for certain what my wampeter was...

And who was in my karass...

And all the good things our karass did for you.

Amen.

Busy busy busy!

Nice review - I read this a few months ago, but didn't comment because I hadn't set up my account yet. Not much to add, but having read all of Vonnegut's books, I enjoyed the chance to reminisce about one of his magnum opi.