Polysecure by Jessica Fern is, as the title suggests, a book about the intersection of attachment theory and polyamory. Fern is a polyamorous clinical psychotherapist and draws a lot of her insights from her practice with nonmonogamous clients. I was skeptical because I’ve often found that books about attachment theory are overly simplistic and treat their readers like children, insisting that attachment styles have bright-line boundaries, clear root causes in childhood, and often imply that natural human diversity in attachment style is immoral. I’m happy to report that my concerns were unfounded. Polysecure is, despite some flaws, a book for adults. Fern treats the subject with nuance, providing useful information but not passing judgment, and presents a creative framework to apply attachment theory to nonmonogamous relationships.

Polysecure avoids, by far, the most common issue with nonfiction books - having a lot of filler. Polysecure has almost no filler. Usually I can sum up a nonfiction book in a few paragraphs, but (as you can probably tell by the length of this review), Polysecure has a lot to say, and Fern doesn’t waste any space by adding extraneous or irrelevant information. Every word is there for a reason.

The book is divided into three parts. The first half deals only with attachment theory and the second half applies that theory to polyamorous relationships. Part Two covers the theory of polysecurity and Part Three offers advice on how to become polysecure.

Part One: Attachment Theory

Nearly all research into attachment theory defines attachment styles which are formed in childhood and remain post-adulthood. Right off the bat, I want to say that I’m skeptical of this entire area of research. Twin studies tend to show that parenting style has very little effect on anything measurable in adulthood, with variation being about half genetic and half non-shared environment, with very little effect from shared environment (which includes family life and parenting style). It would be very unexpected if shared environment show very little effect on anything except adult attachment style. However, there are quite a few studies claiming to show that adult attachment style is related to childhood treatment, and anecdotally, I know a lot of people who can trace their mental & emotional difficulties to parent-child interactions. As a father myself, I take these ideas seriously and, while I’m skeptical of the research, I behave as if my actions have serious consequences down the road. Fern includes a bibliography of books and studies about attachment at the end of her book, but mostly just summarizes the existing literature rather than deep-diving into the evidence, so for the remainder of this review I’ll assume that the research is accurate.

Researchers divide attachment into four distinct styles - one secure and three insecure called anxious, avoidant, and disorganized. Secure attachment is generally presented as the most healthy style, while anxious is presented as unhealthily clingy, avoidant as unhealthily distant, and disorganized as a combination of the other two insecure styles.

Secure Attachment

Secure attachment is formed when childhood attachment needs are met. Fern writes: “A caretaker being present, safe, protective, playful, emotionally attuned and responsive is of paramount importance to a child developing a secure attachment style.” This allows a child to develop “a sense of safety and trust,” and that “the world is a friendly place and… they can ask for what they want because the people in their lives care and are willing to help.” In adulthood, secure attachment manifests in a belief that we can ask for what we want in your relationships, and that our partners will listen, care, and respond with love and support. It also manifests in a healthy amount of flexibility, where if our partners can’t meet our needs, we are able to get them met elsewhere or at a different time.

A child with a secure attachment style will likely grow up into an adult who feels worthy of love and seeks to create meaningful, healthy relationships with people who are physically and emotionally available. Securely functioning adults are comfortable with intimacy, closeness, and their need or desire for others. They don’t fear losing their sense of self or being engulfed by the relationship. For securely attached people, “dependency” is not a dirty word, but a fact of life that can be experienced without losing or compromising the self.

Conversely, securely functioning adults are also comfortable with their independence and personal autonomy. They may miss their partners when they’re not together, but inside they feel fundamentally alright with themselves when they’re alone. They also feel minimal fear of abandonment when temporarily separated from their partner. In other words, securely attached people experience relational object constancy, which is the ability to trust in and maintain an emotional bond with people even during physical or emotional separation.

In childhood, a secure attachment has four “essential features”:

Proximity Maintenance - the ability and desire to be close to our attachment figure(s).

Separation Distress - a healthy amount of distress when separated. This is consistent with most parenting books I’ve read, which claim that it’s ok for a child to be upset when separated from a parent, and that it’s somewhat concerning if a child displays no distress at all.

Safe Haven - a place to go where the child can feel safe when the outside world feels threatening or overwhelming.

Secure Base - a reliable place from which to explore the world and return when the exploring is done.

In adulthood, two additional elements are introduced:

Mutual Caregiving - while children experience asymmetric caregiving, adults in relationships are generally expected to care for one another.

Sexuality - while attachment relationship do not need to involve sexuality, many adult relationships do, and it has profound effects on attachment.

Fern includes a series of caveats in the section on secure attachment that I personally appreciated, given my problems with the book Attached by Amir Levine and Rachel Heller. Given the subject matter, I expected Fern to avoid the overwhelming mononormativity bias of Levine and Heller, but was still worried about this type of essentializing:

I was… unhappy with the presentation of each attachment style being unique to a person instead of unique to a relationship. That is not my experience of attachment styles. With some partners, I have a secure attachment style. With others, I can be anxious or avoidant. It's not because any one of these is my innate attachment style. It is because I am reacting to my partner's feelings and behavior. I have noticed this with other people also. My experience is that people do not have a discrete attachment style that gets implemented with every partner. My experience is that each *relationship* has a certain dynamic where each partner plays out one of the attachment styles, but that the exact same person can have a different attachment style in a different relationship.

Fern addressed my criticism on the nose:

You might function from a more secure style most of the time, but then act out a particular insecure style while under stress, or you might experience different attachment styles depending on who you are relating to…. A partner with a dismissive attachment style might provoke more anxious/preoccupied behaviors from us, or being with a more anxious partner might polarize us into being more dismissive. Our attachment styles can change from one relationship to the next and they can also change within a specific relationship with the same person.

Mercifully, Fern also acknowledges that secure attachment is not merely the province of a lucky few who had the right kind of childhood. Fern stresses that attachment styles are not static and describes “earned secure attachment,” which can be learned as an adult no matter how someone was raised. In fact, much of the book is dedicated to providing a roadmap for getting to a secure style even if we didn’t start out there. She also cautions that attachment styles are not identities with which we should label ourselves or our partners, but rather ways of relating that apply only in certain situations and at certain times. She directs us to identify only with what feels useful and cautions that attachment styles are not excuses for mistreating our partner(s).

Avoidant/Dismissive Attachment

Children with avoidant attachment often appear distant or aloof from parents or other caretakers, even though internally they are experiencing distress. According to the available research, avoidant attachment is caused by parenting that is either neglectful or cold and distant.

When a child does not get enough of the positive attachment responses that they need or they are outright rejected or criticized for having needs, they will adapt by shutting down and deactivating their attachment longings. A child in this scenario learns that, in order to survive, they need to inhibit their attachment bids for proximity or protection in order to prevent the pain and confusion of neglect or rejection. In this situation a child often learns to subsist on emotional crumbs, assuming that the best way to get their needs met by their parent is to act as if they don’t have any.

Fern also mentions something called “expressive dissonance,” where “someone’s facial or verbal expressions are mismatched with their emotional states.” I found that interesting because I’ve never seen it articulated before, but it’s something I strongly identify with. It’s presented as mostly an issue for children, but I experience that kind of dissonance as an adult pretty severely.

Fern also makes sure to point out that avoidant style isn’t always caused by cold or neglectful parents, but can also by caused by “[p]arents who might have the best intentions, but have a child who is so different from them that they are unable to understand or connect with that child in attuned ways.”

Researcher refer to avoidant style in adults as “dismissive.” Dismissive style is characterized by responding to feelings of vulnerability with distance. Intimacy conflict, rejection, criticism, or other kinds of emotional intensity trigger a flight response. Dismissive adults want relationships just as much as anyone else, but “ struggle with their ability to reflect on their own internal experience as well as sensitively respond to the signals of their partners.” Healing a dismissive style involves getting in touch with one’s own emotions and needs, learning how to self-soothe, and developing an embodied sense that it’s ok to feel strong emotions or rely on others.

Anxious/Preoccupied Attachment

Anxious children show an attachment system that is hyperactivated. They cling to their parents and are reluctant to venture away from them even in safe situations.

Parents who are loving but inconsistent can encourage the adaptation of the anxious style. Sometimes the parent is here and available, attuned and responsive, but then other times they are emotionally unavailable, mis-attuned or even intrusive, leaving the child confused and uncertain as to whether their parent is going to comfort them, ignore them, reward them or punish them for the very same behavior. This unpredictability can be very dys-regulating for a child who is trying to stabilize a bond with their caregiver so, in an attempt to cope, they then learn that hyperactivating their attachment system through getting louder or needier achieves the attention they need. In this scenario, the child can become dependent on their hyperactivating strategy in order to survive, fearing that if they let their attachment system settle and rest then their needs will never be met. This in turn can lead to a chronically activated attachment system that exaggerates threats of potential abandonment, which may or may not actually be there.

Anxious style can be caused by parents who are unable to co-regulate emotions with their child, parents who overshare about their own emotions (thus making the child responsible for the parent’s well-being), parents who discourage autonomy, or parents who overstimulate their child.

Researcher refer to anxious style in adults as “preoccupied.” Fern uses a lot of academic language to describe preoccupied style, but it’s basically summed up as “clinginess.”

they may end up constantly monitoring their partners’ level of availability, interest and responsiveness. The partner of someone with a preoccupied attachment style may then feel like this constant tracking of relational misattunements and mistakes is controlling of them. But for the person with a preoccupied attachment style, this behavior is less an attempt to overtly control their partner than it is a symptom of their attachment system being overly sensitive to even the slightest sign they might be left. From their perspective, they’re not trying to control their partner; they’re just grasping for a relationship they’re afraid is slipping out of their hands.

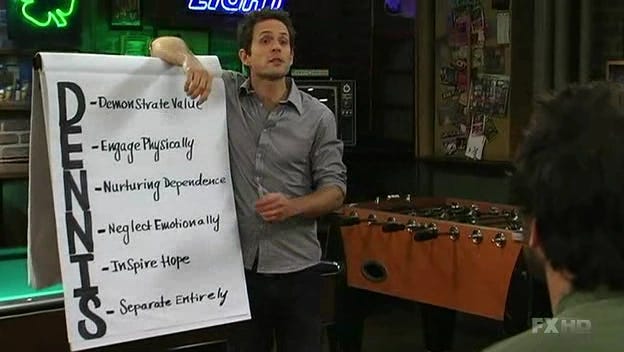

Preoccupied adults often jump into relationships too quickly and ignore red flags due to fear of abandonment or discomfort with being alone. They will often engage in compulsive caretaking behaviors, but not necessarily in ways that are attuned with their partners’ needs, seeing caretaking as a way to create value, promote dependency, or just avoid feeling lonely. I definitely do this. When I find myself attached to a partner who is behaving dismissively, I tend to respond with a preoccupied style. My mind immediately goes toward thinking of ways I can show my value by providing care or meeting some unexpressed need. Sadly, this mostly just results in more dismissive behavior.

Healing a preoccupied style involves developing a strong sense of self apart from relationships with anyone else. Preoccupied adults can heal by learning to trust themselves and derive authority and validation internally.

Disorganized/Fearful-Avoidant Attachment

Disorganized attachment is a combination of the other styles.

Children with a disorganized attachment style have an attachment system that seems to be hyperactivated and deactivated at the same time. They don’t display a consistent organized attachment strategy in the same way that children with a secure, anxious or avoidant style do. Instead, they seemed to lack a coherent organization of which strategy to employ, often vacillating between the anxious and avoidant insecure attachment styles.

Fern describes this style as “one foot on the gas, one foot on the brake.” Disorganized style typically arises when children see their parents or other caregivers as sources of safety and security and scary or threatening at different time, or even at the same time. This leads to the attachment system and the defensive systems getting activated at the same time. Fern claims that 20-40% of the general population has the disorganized style and 80% of abused children develop it. Disorganized style can also be caused when a child has special needs or hypersensitivity that leads the world to be confusing or overwhelming.

Researchers refer to disorganized style in adults as “fearful-avoidant.”

People with this insecure attachment style have the characteristics of both the dismissive and preoccupied styles—their desire for closeness and their longing for connection are active, but because they have previous experiences of the ones they loved or depended on hurting them, they tend to feel uncomfortable relying on others or are even paralyzed by the fear that speaking their feelings and needs could be dangerous and make things worse. They might request attention from a partner but then withdraw when connection is offered or, in more extreme manifestations, they might demand attention or affection and then attack or criticize their partner when what they want is given. People with this style are easily overwhelmed by their feelings or subject to what I call emotional flare-ups, where their intense emotional states can take over, disrupting their ability to function and, at times, taking others down with them.

Fern makes a distinction between internal and external styles of fearful-avoidant attachment. People with the internal style tend to experience massive internal stress but do not act out in destructive ways. People with the external style tend to act out their distress by behaving in confusing, contradictory, or harmful ways.

Attachment Dimensions

Rather than relying on the four distinct styles, Fern suggests viewing attachment as existing along two axes: anxiety and avoidance. A person’s attachment style at any given moment can exist at different points along the high/low anxiety spectrum and the high/low avoidance spectrum. Secure attachment is low anxiety and low avoidance.

Fern reports that when she uses this model with her clients, they can more easily place themselves along the axes and feel less pathologized.

Fern also notes that the axes can be seen not through their dysfunctions, but through their desires. Insecure attachment styles are not just survival strategies or reactions to distress. “At their root, they can also be expressions of the essential human desires for autonomy and connection.” High avoidance can instead be characterized as a strong desire for autonomy and agency. High anxiety can be characterized as a strong desire for connection and togetherness. Problems only arise when these desires go too far and become isolation or codependence. I appreciated this section because it address one of my other criticisms of Attached:

[The books shows] favoritism toward anxious attachment style over avoidant. Partners of people with anxious attachment style are encouraged just to accommodate their partner's clinginess, constant need for reassurance, possessiveness, and jealousy, while partners of people with avoidant attachment style are encouraged to leave the relationship or else accept that they will never be completely happy. There is very little advice given on how to make an avoidant partner feel safe experiencing intimacy. Most advice regarding avoidant style is on how to change it.

Fern doesn’t fall into this trap. She discusses attachment styles with mostly morally neutral language and stresses that a need for autonomy or connection is totally fine, and it only becomes a problem if it starts causing us distress or conflict. In fact, Fern suggests viewing autonomy and connection and both vital to a healthy relationship, and analogizes them to two reins of a horse:

If we want to turn left, we tighten our grip to tug on the left rein, simultaneously loosening the other rein. We do the opposite to move right. The terrain ahead is constantly changing, and so the reins in our hands are constantly readjusting. With time and practice, we gain the ability to simultaneously tighten and loosen the reins without tightening so hard that we hurt or jerk the horse, or loosening so much so that communication and direction are lost.

To best respond to whatever arises in front of us day by day or even moment by moment, we sometimes need to tighten up on the reins of autonomy, while loosening the reins of connection. In other moments, we tighten the connection reins, moving in closer to our partners while releasing the autonomy reins…. With practice, we learn that autonomy and connection aren’t an either/or experience but a both/and experience. We can be both different and connected. With practice we can also learn how to ebb and flow between the two states with more skill and grace, using both reins simultaneously to embrace both our independence and our dependency, our autonomy and our connection.

Fern stresses that healthy boundaries are key to healthy attachments. I appreciated this section as well, because I’ve long believed that establishing and enforcing boundaries is an important part of any relationship, be it employment, friendship, dependent, romantic, or any other type. Clarity about what kind of treatment all parties will accept and what they are willing to do is the hallmark of a healthy relationship. Fern agrees, and describes healthy boundaries as those that leave us connected and protected. Porous boundaries leave us connected but not protected, while rigid boundaries leave us protected, but not connected.

The Nested Model of Attachment and Trauma

In Chapter Three, Fern proposes a model of attachment that goes beyond the interpersonal level and expands out to cover a person’s relationship with self, and various level of environment:

Fern refers to this as the nested model of attachment and trauma. She sees attachment and trauma as inherently linked because “the absence of safe nurturing relationships can lead to trauma, and having safe and nurturing relationships can serve as a shield in the face of other traumas.” To truly understand attachment and trauma, Fern claims, we must expand our view past the self and relationship stages and consider additional levels of interaction which affect how we experience trauma and attachment. The levels are:

Self: this includes your temperament, genetic expressions, history, skills, and interior experiences.

Relationships: this level includes one-on-one interpersonal relationships with family, friends, lovers, and partners. While attachment wounds can be incurred at any level, Fern claims that they can be healed at this level. She also stresses that romantic/sexual partners are not necessary for this process, and that close friends and siblings can offer provide corrective attachment experiences to heal past attachment traumas.

Home: this level includes “the number of people in your home, the type of home culture and place you grew up in, how many generations of family were living in your home, whether you had to go back and forth between your parents’ homes due to separation or divorce and whether or not you even had a home.” Our home life, including the social but also the physical aspects, can heavily influence our sense of belonging and our sense of safety with ourselves and others.

Local Culture and Communities: this level includes places and institutions outside of our home such as “work, school, friends’ houses, the gym and clubs, as well as sports venues and religious or spiritual centers.” Fern also includes “virtual culture and online communities.” Each of these communities have norms which may or may not work for us, and how well we fit may affect our experiences of attachment and trauma.

Social Level: this level includes “the larger societal structures and systems that we live in, such as our economic, legal, medical and political systems, as well as our religious institutions.” This is the level where things like “structural oppression” and discrimination come into play. Fern describes how racism, homophobia, sexism, patriarchy, and capitalism can all cause trauma and influence our ability to securely attach.

Global or Collective Level: this level refers to “our original mother: Mother Earth.” Fern suggest that “climate trauma” or a lack of green spaces can be traumatizing and inhibit our ability to securely attach. This level also includes “collective trauma” such as “ slavery, genocide, famine, war or the subjugation of women,” which not only affect the people experiencing it, but can “alter the expression of DNA, making subsequent generations more susceptible to certain health issues, increased anxiety, PTSD and wariness to danger.”

I don’t know how useful this section of the book was. Fern doesn’t really say anything inaccurate, but she doesn’t say anything particularly helpful either. By her own admission, almost all attachment research focuses on the self and relationship level, so most of the discussion of the higher levels comes off as conjecture. Much of it seems mostly like an excuse to engage in left-wing activism, which is disappointing because up until this section, there was very little politics. Thanks to this section, I’ll have to be cautious about recommending this book to anyone who doesn’t share Fern’s views on structural discrimination, feminism, or climate change. She even takes a weird potshot at capitalism:

Is it honestly possible to feel safe and secure in a capitalist society that defines our human value based on what we do and how much we make, rather than who we are? Is it honestly possible to feel safe and secure in a society that bombards us with messages asserting (even aggressing) that in order to be secure in our self or with our place in the world we need to acquire more money, more religion, more objects, more products, more body-altering procedures or more property?

Ummm…. yes? People do it every day. Not to get into a big defense of capitalism, but I promise you it’s easier to feel secure in capitalist societies than societies like China or the USSR which tried alternatives.

The nested model has some explanatory power, but it seems to single out specific issues, almost all of which suspiciously align with the social justice fundamentalist view of the world, from the infinite issues that can cause trauma or affect one’s ability to attach. Fern calls out left-wing issues like racism and homophobia, but ignores right-coded issues like government intrusion into private lives, anxiety over a rapidly changing world, or one of the biggest attachment-related anxieties people have - cancelation. Huge numbers of people regularly report that they feel unable to share their opinions or feelings because they will be rejected or abandoned by their peers, but that doesn’t appear anywhere in the discussion.

That’s not to say that Fern should have included these issues. It’s just to point out that there are endless issues that can cause trauma or affect someone’s ability to securely attach, and it doesn’t seem terribly useful to discuss a handful of them specifically, especially not when it’s such a jarring injection of politics into an otherwise apolitical book. I think this book probably would have been better without this section, and maybe just a short paragraph or two describing how everyone’s issues are different, and there are countless reasons why someone may be experiencing attachment insecurity which should be explored with a therapist or the people close to you.

Part Two: Consensual Nonmonogamy

The second half of the book is about applying attachment theory to consensually nonmonogamous (“CNM”) relationships. Fern begins by discussing the motivations of people who choose nonmonogamy and the benefit they feel they receive:

Both [monogamous and CNM people] had the relationship benefits of family, trust, love, sex, commitment and communication, regardless of whether they were in a monogamous or nonmonogamous relationship. However, people in CNM relationships additionally expressed having the distinct relationship benefits of increased need fulfillment, variety of nonsexual activities and personal growth. Instead of expecting one partner to meet all of their needs, people engaged in CNM felt that a major advantage of being nonmonogamous was the ability to have their different needs met by more than one person, as well as being able to experience a variety of nonsexual activities that one relationship may not fulfill. The other notable relationship benefit unique to people in CNM relationships was personal growth—people reported feeling that being nonmonogamous afforded them increased freedom from restriction, self and sexual expression and the ability to grow and develop.

Fern also included that in her own practice, her clients consistently name three other reasons for choosing CNM: “sexual diversity, philosophical views and because CNM is a more authentic expression of who they are.” I appreciated that Fern especially singled out sexual needs as acceptable and totally fine. In public, polyamorous people tend to stress their interest in loving relationships and downplay their interest in sex.

To me, this is an unfortunate symptomatic expression of our sex-negative culture that shames us for our basic human needs, desires and sexuality. There are people who genuinely need and want sexual diversity and it is not because they are sexually deviant, avoidantly attached, addicted to sex or noncommittal. Instead, they are people who embrace their sexuality and the diverse desires and expressions that it may encompass and require.

It’s not often that I see a full-throated defense of sexuality, and I like that Fern didn’t mince words or hedge. She also noted that some people choose CNM for philosophical reasons, though she spoke about it in terms of patriarchy and privilege rather than the framing of autonomy and individualism that I prefer.

She also neatly sidestepped the (mostly pointless) debate about whether nonmonogamy is a lifestyle choice or an orientation by simply acknowledging that some people see CNM as an “expression of their fundamental self,” and that for those people, it’s more of an orientation, but for other people, it’s a lifestyle.

The introductory chapter finishes with a discussion of the different types of CNM

Fern went on to describe each type. People who are familiar with all of these terms should feel free to skip this part, as it was mostly 101-level information.

Attachment and Nonmonogamy

Fern starts by acknowledging that most attachment research is blatantly mononormative. Attachment researchers tend to equate anything other than a vanilla, monogamous relationship as evidence of insecure attachment. Some authors go so far as to declare that “healthy, satisfying relationships are, by definition, dyadic.” Fern specifically called out the idea of Stan Tatkin’s “couple bubble” and agrees with me that a good amount of it sounds like codependency in disguise. All of this is despite the fact that there is very little actual research on CNM and attachment, and the few studies that have been done “ demonstrates that people in CNM relationships are just as likely to be securely attached as people in monogamous relationships,” and may actually be lower in attachment avoidance. Interestingly, one study found that having an insecure style in one relationship was not predictive of attachment style in other relationships, reinforcing my theory that attachment styles tend to be a characteristic of relationships, not people. Fern acknowledges, however, that the small amount of research done is insufficient and leaves many unanswered questions.

One of my favorite passages from the book comes during a discussion of attempting to apply Stan Tatkin’s PACT method to CNM couples. One of my biggest criticisms of Tatkin was that his advice tends to focus too much on formality and structure, which can lead people to simply perform the role they’ve been assigned rather than authentically express themselves. Fern has similar criticism:

my critique… is that it is relying too much on the structure of the relationship to ensure and safeguard secure attachment instead of the quality of relating between partners to forge secure attachment. When we rely on the structure of our relationship, whether that is through being monogamous with someone or practicing hierarchical forms of CNM, we run the risk of forgetting that secure attachment is an embodied expression built upon how we consistently respond and attune to each other, not something that gets created through structure and hierarchy. Secure attachment is created through the quality of experience we have with our partners, not through the notion or the fact of either being married or being a primary partner…. Relationship structure does not guarantee emotional security.

Polysecurity

Fern coined the term “polysecure” to describe her clients who generally only needed short-term help to deal with a new situation, breakup, or other stressful situation, then went back to thriving in their relationships. These people had secure attachments with themselves and their partners.

Polysecurity is not automatic. Many couples who transition from monogamy to CNM had secure attachments while monogamous, but had their security challenged or broken by the transition. This is often exacerbated by friends, family, community, and therapists who see this as evidence that they should go back to being monogamous.

To me, telling people who are struggling with the transition from monogamy to CNM to go back to monogamy because CNM is just too difficult would be like telling the new parents of an infant who are struggling without sleep or personal time that maybe they should just send the kid back since they didn’t have any of these issues before the child arrived. This analogy may seem ridiculous because you literally can’t send the kid back, but that can be exactly what it can feel like for people who have made the transition out of monogamy into CNM, especially for people who experience CNM not as a lifestyle choice but as who they fundamentally are.

Fern stresses that relationship difficulties during the transition are normal and expected, not because CNM is inherently difficult or chaotic, but because it involves a massive paradigm shift and very few resources or support systems to help. “Almost every aspect of love, romance, sex, partnership and family now has a different set of expectations, practices, codes of conduct and even language compared to the dominant monogamous paradigm of relationships.” This kind of shift can cause friction and can also expose preexisting issues that would have eventually caused serious problems anyway. The shift can also expose preexisting attachment insecurity that were hidden or mitigated by the relationship structure. Many couples are able to navigate the transition, but many are not.

I will add that the transition from monogamy to nonmonogamy can also cause breakups for good reasons. Something I’ve seen several times is that a person is in an unfulfilling or unsatisfying relationship, but accepts it because they think all relationships are like that or that better treatment is not available to them. Opening the relationship can allowed them to experience, in an embodied way, different relationships, which often leads to the realization that their former relationship was not meeting their needs.

Issues Unique to Nonmonogamy

Fern points out that nonmonogamy has some insecurity build into it. “In CNM, we don’t have the security of knowing that a partner is with us because they see us as the best, one or only partner out there for them.” She adds, however, that many prefer this to the potentially-artificial security of monogamy or other forms of structure. Personally I agree with Fern when she says “I find security in the fact that when I’m in CNM relationships I know that my partners are not with me because they are obliged to be, but because they continue to choose to be.”

Fern points out that CNM relationships can “replicate the conditions of attachment insecurity.” This is a clever way of salvaging the attachment studies that assume that nonmonogamy is a symptom of avoidance. She’s able to acknowledge that going on dates, experiencing new relationship energy, or entering into additional relationships are not necessarily symptoms of dismissive attachment, they can lead people to “become less available, responsive or attuned to their pre-existing partners.” There can also be ruptures due to other people’s reactions or the loss of status that comes along with a transition to nonmonogamy. This can leave the other partner feeling disconnected, and can trigger a preoccupied style. This sometimes gets labeled as jealousy, but often it’s just a reaction to a partner being less available, responsive, or attuned, and if unaddressed can trigger a panic response. Sometimes, just realizing this is what’s happening is enough to fix the issue, sometimes partners need to work together (or with a professional) to figure out ways to be more present, and sometimes it means couples need to transition to a lower level of intimacy or break up.

Disorganized attachment can also be triggered in ways unique to CNM relationships:

As the relationship opens, a partner’s actions with other people (even ethical ones that were agreed upon) can become a source of distress and pose an emotional threat. Everything that this person is doing with other people can become a source of intense fear and insecurity for their pre-existing partner, catapulting them into the paradoxical disorganized dilemma of wanting comfort and safety from the very same person who is triggering their threat response. Again, the partner may be doing exactly what the couple consented to and acting within their negotiated agreements, but for the pre-existing partner, their primary attachment figure being away, unavailable and potentially sharing levels of intimacy with another person registers as a debilitating threat in the nervous system.

Such a response can lead a partner to act out in destructive ways. Fern recommends hiring a professional at that point.

I really liked the section on insecurities unique to CNM. I’ve experienced the cycle of new partner —> existing partner becomes anxious and starts demanding more attention —> partner’s anxiety triggers my avoidance and I resist. I’ve also experienced it as the anxious partner. It’s tough to break out of, and thinking about in in terms of attachment seems helpful. It’s also nice to see Fern attempt to synthesize the attachment research which assumes that monogamy is the only healthy option and apply it in a poly-friendly context.

Fern also goes through each level of the nested model and discusses particular issues which can be activated by CNM. It’s somewhat interesting, but it’s mostly a bulleted list of problems you might encounter, so only really helpful if you’re experiencing one of the listed problems and feel validated by seeing it called out. I suppose you could also use it to familiarize yourself with potential issues you might encounter before opening up, but honestly, that seems like it’s asking for anxiety.

Attachment-Based Relationships

Fern makes a distinction between what she calls “attachment-based relationships” and relationships that aren’t attachment-based.

There is a difference between being in a secure connection with someone and having a securely attached relationship. Secure connections are with people or partners who we don’t have daily or regular contact with, but with whom we know that when we reach out it will feel as if a moment hasn’t passed. We are secure in the bond that we have with such people, and this bond might be immensely meaningful, special and important to us, but it’s not necessarily a relationship that requires us to invest regular maintenance and attention. In CNM, these might be the partners we refer to as comets, satellites or casual. They’re the people who we see at special events a few times a year or our less-involved long-distance relationships. Securely attached relationships are based on consistency and reliability.

Throughout the book, Fern refers back to this concept of attachment-based relationships, often stating that certain advice or principles only apply to attachment-based relationships. Fern recommends that people in relationships are clear about whether they want or expect the other person to be an attachment figure for them, and warns that pain and confusion can result if there is a mismatch in expectations. She also recommends “honestly assessing if the partner has enough time, capacity and/or space in their life and other relationships to show up to the degree required for being polysecure together.” She finds that once people clearly communicate about whether they are pursuing an attachment-based relationship, all parties can more easily orient themselves.

I question the wisdom of this particular classification. I’m a relationship anarchist, and one of the reasons for that is that I think proscriptively labeling relationships tends to create more confusion than understanding. One of the things I love about relationship anarchy is that it doesn’t require one to fit into rigid categories. Relationships can be whatever the people in them want the relationship to be. Fern’s conception of “attachment-based relationships” seems to be similar to the mononormative impulse to categorize relationships into “serious” or “not serious.” Calling someone an “attachment figure” seems functionally the same as calling them a boyfriend or girlfriend, and treating that label as immensely meaningful.

All of my relationships involve some degree of attachment, otherwise I wouldn’t have them. When she draws this kind of distinction, Fern seems to be suggesting that what she calls a “secure connection” is categorically different from a secure attachment. I don’t find it a useful distinction. I struggle to imagine how it helps to tell a person that I’d like them to be an attachment figure. What does that mean? Daily contact? Some level of commitment? Ditto for a non-attachment figure. Does that mean I don’t expect reliability and consistency? In my experience, feeling secure about any relationship, even if it’s with someone I don’t see that often, takes reliability and consistency.

I also reject the idea that it’s not possible to have a secure attachment with a person you don’t have regular contact with. I don’t have to know when I’m going to see a person to know that they care about me and that I can rely on them. A person can be a safe haven and a secure base even if they’re not always present, so long as I know that they will be there for me when I need them.

The main reason I try to avoid proscriptive labels is that they don’t necessarily mean the same thing to all parties. Rather than call someone an attachment figure, I think it’s much better to taboo all labels and instead talk directly about what our desires and expectations are. That way, we’re not using ambiguous categories to obscure what we really mean, and we can be sure everyone is on the same page.

Part Three: How to Become Polysecure

Fern begins by cautioning that this section is only for people in attachment-based relationships. She recognizes that this doesn’t require a lifetime commitment or cohabitation, but that it does involve “some level of commitment to being in a relationship together.” Usually, I object to the term “commitment,” as I prefer expectation-setting or making predictions, but it’s unclear what “commitment” actually means here. I usually interpret it as some kind of promise or guarantee to do something, but Fern includes things like “sharing intimate details,” “helping your partners with moving,” or “offering physical, logistical, or emotional support” as ways of demonstrating commitment. To me, those sound like ways of showing that you care about a person, not promises or obligations, so I’m not sure what kind of commitment Fern is talking about.

Being a Safe Haven and a Secure Base

Fern reports that a key part of forming a secure attachment is for partners to be a safe haven and a secure base for each other. A person is a safe haven when they “care about our safety, seek to respond to our distress, help us to co-regulate and soothe and are a source of emotional and physical support and comfort.” Fern claims that people who have a safe haven relationship are more resilient and more easily recover from trauma.

A secure base “provides the platform from which we can move out in the larger world, explore and take risks.” Secure base partners encourage each other’s autonomy, growth, and exploration, even if it requires time apart. They “ will not only support our explorations, but will also offer guidance when solicited and lovingly call us on our shit.” Fern sees “being a safe haven as serving the role of accepting and being with me as I am, and a secure base as supporting me to grow beyond who I am.”

Fern also notes that people in CNM relationships don’t have to provide or receive all aspects of the safe haven and secure base from a single partner. Some partners may be better at accepting us as we are, while others may push us to grow and improve. She also notes that not everyone needs this from partners. Some people can serve as their own safe haven or secure base.

These are great insights, and are totally consistent with my experience.

The HEARTS System

Fern proposes a number of specific things that we can do to facilitate forming secure attachments in CNM relationships, using the acronym HEARTS.

H - Here (being present)

Fern argues that presence is about more than just physical proximity - it involves giving focus and full attention, listening, and responding to our partners in a fully embodied way. Physical proximity is important and necessary, she says, but quality of the presence is just as important. If you’re only half paying attention or are distracted by other things (or in the case of CNM, other people), it will cause attachment difficulties.

I agree that presence is a necessary ingredient for secure attachment, but I disagree that presence requires physical proximity or that quality time necessarily requires one’s full attention to be on their partner. Long-distance relationships are difficult and present unique challenges, but Fern seems to be suggesting that such relationships are unable to achieve secure attachment, which is not true in my experience. Advances in technology have made physical proximity much less important than it used to be. Some people require it, but other people can get by with long physical separations.

Likewise, I think that being fully focused and attentive is important in some circumstances, but I don’t think it’s required in everyday interactions. Most of the quality time I have with my wife involves us sitting on the couch watching tv, playing video games, or reading, and interacting throughout such activities. Parallel play is important, and partners that constantly demand full attention because that’s their only concept of “quality time” are displaying preoccupied attachment. I have ADHD, and it’s often uncomfortable for me to just have a conversation with someone while not doing anything else. I can actually pay more attention to a conversation if I have something else occupying my eyes or hands.

There should always be some circumstances where partners are fully attentive to one another, without any distractions, but those don’t have to be the norm, and I think it’s equally important for partners to be able to value being together even if they’re not getting one another’s full attention.

E - Expressed Delight

Fern argues that it’s essential for partners relationships to show the ways they they are special and valuable to each other. “We can express the delight we have for our partners through our words, our actions, our touch, as well as just the look in our eyes.” Expressed delight is especially vital in CNM relationships because “The paradigm shift from the monogamous mindset of I am with you because you are the only one for me to the nonmonogamous view that I am with you because you are special and unique, but not the only one, can be difficult to grasp.” This shift in thinking requires partners to show each other that they are wanted and valued, and it “can be an important resource to lean on when feeling jealous or threatened by a metamour or potential new partners.”

I completely agree with this, and would only caution that all such expressions must be authentic and spontaneous. You don’t want to end up putting on a performance, as I discussed in my review of Wired for Love:

One of the worst things people can do in relationships is put on a performance rather than show vulnerability. Performing a role removes the potential for genuine intimacy by hiding one’s true self. When you put on a performance, your partner is no longer interacting with you - they are interacting with the character that you’re playing. Even worse, once you start performing a role, you can get trapped in it. It becomes psychologically impossible to stop, and the pressure to keep acting in an unnatural way creates stress and resentment, which poison the relationship. Partners sometimes spend their entire relationship pretending to be different people until the resentment grows too large and they flame out, often causing trauma or leaving partners hating each other.

So long as your expressions of delight are genuine, they are indispensable to a securely attached nonmonogamous relationship.

A - Attunement

Attunement is somewhat difficult to describe, as it’s more of an abstract idea than a concrete action. Fern describes it as “a state of resonance with our partners and the act of turning towards them in an attempt to understand the fullness of their perspective and experience.” If you’re having trouble parsing exactly what that means, I’m right there with you, but I think it’s a critically important idea, so I’ll try to break it down.

I think attunement is related to Stan Tatkin’s idea of becoming an expert on your partner. It is about getting to know their genuine self, not the person they present to the outside world or when they feel unsafe. It is about avoiding creating a backwards connection with a pretend person as described in Patricia Evans’ Controlling People.

In relationships, there is a near-universal impulse, especially early on, to treat our partners as though they are the people we wish they were. Attunement is about cutting through that illusion, seeing the real person underneath, and accepting and valuing that person. Attuned partners will feel as though they are always on the same team, and will intuitively take one another’s perspectives and well-being into account when making decisions.

R - Rituals and Routines

Fern stresses the importance of routines in daily life and rituals to mark important moments. This can help establish the consistency and reliability that fuels a secure connection. This is especially important in nonmonogamous relationship, as Fern explains:

In monogamy, the daily routines of a relationship can be easier to fall into. There are only two people to consider, and the larger rituals and relationship rites of passage such as marriage, having children or moving in together are more obvious, culturally expected and supported. In nonmonogamy, socially recognized ways of honoring the relationship can be less clear, and it can be more difficult to find our rhythm with a partner, especially when we don’t live with our partner and/or when one of you already lives with other partners.

This where you really see Tatkin’s influence on Fern. He has an entire chapter in Wired for Love devoted to rituals which sounds very similar to Fern’s ideas here. Here is what I said about Tatkin’s advice:

My view is that intimacy (much like greatness) cannot be planned. Just performing the motions of intimacy won’t make it happen. Sincere expressions of intimacy have to come from the heart. When partners have effective intimacy rituals, it’s because they arose spontaneously as expressions of affection. The ritual doesn’t create intimacy, it is a byproduct of intimacy that was already there, and merely reinforces the love and affection that partners already feel for one another. If partners try to plan an intimacy ritual rather than letting one arise spontaneously, they run the risk of just performing intimacy instead of actually feeling it.

Tatkin’s advice may be helpful to people who feel as though they want to express their affection and aren’t sure how. A person may read this advice and get inspired to show love for their partner in a new way. But it also could read as encouraging partners to just play the role of loving partner without really feeling it, which is the kind of thing that can ruin relationships.

Fern also, unfortunately in my opinion, expresses support for the idea that couples can have “certain things or places that only belong to one relationship.” She acknowledges that “these waters can become dangerous and hierarchical very quickly” but claims that it can work well “as long as it’s transparent and understood to everyone involved what things belong to a certain relationship and why.” Personally, I’ve never seen that work well. It’s perfectly natural and expected to have certain special activities, pet names, or whatever with one partner and not others, but to be healthy, that needs to be an authentic expression of the relationship. If you’re avoiding certain things because you’re worried about upsetting another partner, that’s not a genuine expressing of affection - it’s just the performance of one.

Fern stresses that rituals or routines about parting and reuniting are especially important. “Our attachment systems are very sensitive to comings and goings. Abrupt departures and sudden arrivals can all be jarring to the nervous system, and hellos or goodbyes left unacknowledged can be disconnective.” This can be especially important in nonmonogamous relationships because often these moments of parting or reuniting can come before or after seeing another partner. How that happens can have a profound effect on how secure of a base a partner can be.

I agree that parting, and especially reuniting, are important to an attachment system. You never want your partner to feel happy you’re gone or sad that you’re back. I try to always address any negativity anyone feels before we’re separated, and I always make extra sure that if I have frustration or negativity to express to a partner, I avoid doing it when we’ve been reunited. I want our reunion to be a positive experience every time. Nothing feels worse than a partner coming in the door and immediately bringing the mood down. Difficult conversations can wait ten minutes until after we’ve expressed some (genuine) delight or affection at seeing each other.

My four-year-old daughter is intuitively awesome at this. You will never see her happier than when she’s been reunited with her parents. Even if she’s upset or otherwise in a bad mood, when I first see her she will smile and scream “DADDY!” at the top of her lungs and want a hug before she gets into what’s bothering her. I recommend we all learn from her example.

T - Turning Towards after Conflict

“When there is conflict and disagreement or when attunement and connection have been lost, it is how we repair and find our way back to our partners that builds secure attachment and relational resilience.” People in secure attachments are more likely to demonstrate “their joint concern for their own interests and their partner’s interests as well as for enhancing the relationship.” Happy couples argue just as much as unhappy couples, but they are faster to admit responsibility, begin the healing process, and learn from their mistakes.

I often tell couples and multiple-partner relationships that you can have all the communication techniques and conflict resolution skills in the world, but they do nothing if you still have an attitude of wanting to either be right or prove your partner wrong. I still recommend acquiring more communication and conflict resolution skills, but even without these, the right attitude—one of repair responsibility, humility and openness—goes far.

This is one of the areas where I tend to worry that relationship counselors are confusing the cause and effect. Partners approach conflicts with concern for their partners’ interests because they already care about their partners’ interests. There’s no “one neat trick” to doing that. If you care more about getting your way than finding win-win solutions, no relationship advice is going to change that. Love is all.

Thankfully, Fern mostly acknowledges this, and her advice is more practical, including things such as speaking irl if a text conversation is getting heated, reminding yourself of what’s important, and having conversations about how to handle conflicts before you’re in them. It’s all pretty unobjectionable.

S - Secure Attachment with Self

When we have experienced attachment insecurity with caregivers—whether in childhood, in our adult relationships or as disruptions in any of the levels discussed in the nested model of attachment and trauma—our primary relationship with our self can become severed and the development of certain capacities and skills can become compromised. Attachment ruptures and trauma can also leave lasting marks on our psyche, distorting our sense of self through the beliefs that we do not matter, that we are flawed, broken, unworthy or too much while, simultaneously, not enough. This is what needs to be repaired, and in many ways it is the only aspect of our healing that we are truly in control of.

Self-attachment is critically important because even the best relationships are not guaranteed to last forever, and, contra Tatkin, “even when partners are actively involved with you it is unrealistic to expect them to be there for you every time you are in need.” While partners can be the inspiration of our feelings of hope, love, strength, emotional regulation, and purpose, they are not the source of these things. We are the source of these things for ourselves. Self-attachment is especially important in polyamorous relationships:

In polyamory, we need the internal security of being anchored in our inner strength and inner nurturer to navigate a relationship structure that is considerably less secure. Inner security is also imperative because depending on a certain partner as our only go-to support system regarding our relationship with another partner, a shared partner or one of their partners can be triangulating, messy, inappropriate, divisive and even damaging. You must be a priority in your own life.

Even if we don’t have a secure self-attachment, we can earn one through “creating a coherent narrative of our past experiences.” This can be especially difficult in CNM relationships because we don’t have cultural narratives to fit our relationship traumas or painful breakups into. Fern suggests not only describing your experiences, but developing an appreciated for the coping mechanisms you used. “Your attachment adaptations are what worked best in the environment that you were embedded in, and it is important to recognize the power and wisdom in the different styles that you constructed.”

Fern also stresses that developing a secure self-attachment also requires the rest of the HEARTS method, just directed at yourself. We must actually be present with ourselves and pay attention to what is happening in our bodies and minds. We must express delight for ourselves and appreciate the things that are valuable about us. We must truly get to know ourselves and attune our conscious mind with what we are actually feeling, thinking, and experiencing. We must pay attention to our inner rhythms and figure out what routines or rituals best support ourselves. And we must treat ourselves with kindness and understanding when we make mistakes or fall short of our ideals.

I am probably uniquely unqualified to comment on this section. I was blessed with a secure attachment with myself for as long as I can remember, so I have never needed to earn that. Fern’s account seems very plausible to me, though, so I encourage anyone who feels an insecure self-attachment to take her advice.

Final Thoughts

Fern closes the book by discussing whether couples should “close” their relationship if they are having attachment problems. She is mostly ambivalent, noting that it works for some people and not others. She also notes that

attachment healing does not happen overnight and there will probably never be a point where you are 100 percent healed and feel absolutely ready to open up again, so at some point you will have to face the discomfort of moving forward into nonmonogamy.

Personally, I don’t recommend closing a relationship unless both partners are ok with it staying closed indefinitely. In my experience, the only way to get more comfortable with nonmonogamy is to be nonmonogamous and confront your fears head-on. When the worst doesn’t happen, you become less and less afraid that it will. Comfort comes from experience. Most people who close their relationships never develop that comfort because they aren’t able to have those experiences. It forever remains a distant, anxiety-inducing idea. Closing a relationship also sucks because it means breaking up with all other partners for hierarchical reasons. I don’t recommend treating people you care about that way.

Fern ends the book with the hope “that this book will challenge the monogamous presupposition that attachment theory primarily functions under and that some of the concepts covered are beneficial to people both monogamous and nonmonogamous.” Despite my objections, I think she’s done that brilliantly. I strongly recommend this book to anyone practicing or considering nonmonogamy. I’ve summarized the ideas here, but even after nearly 10,000 words, there is so much more in the book that I wasn’t able to include. Give it a read. It’s worth it.